Real power lies not with elected politicians but with unelected central bankers

When, why and how did the central banks abrogate the responsibilities of government?

Half a century ago, when still supposedly a bright eyed and bushy tailed undergraduate at the University of Manchester, then a hotbed of left-wing political thought, I was set the essay “Is Britain becoming ungovernable?”

The trades unions were on a rip and Margaret Thatcher was yet to emerge. The question to be answered was no doubt supposed to be focussing on where true power in the country was vested and what role parliament and government had to play when the agenda is defined by extra-parliamentary forces.

It was the era of wildcat strikes, uncollected garbage and unburied bodies. It was in many respects not a happy time although beer and cigarettes were cheap and, as perchance the flat my parents owned and in which I was living was right next to one of Manchester’s largest hospitals and we were on their power supply circuit, when there was another bout of industrial action that cut off electricity, I never lost mine. Having heat, light and hot water when nearly all others didn’t, made me very popular amongst the fillies.

Michel Barnier’s government has fallen. It was doomed from Day One and I can still not work out in my head what Young Macron can have been thinking when he called him to the Elysée Palace, tasking him with turning around the country which Macron himself has presided over with unfathomable incompetence for over seven years.

Back in 2017, and just after Macron had travelled to London in pursuit of the votes of the many tens of thousands of French citizens who were living here I found myself in disagreement with an old friend, a fervent Francophile, who had met him in the City and who thought the sun shone out from all of his orifices whilst I, cynic that I am, saw nothing but an ambitious windbag.

Alas, I wonder whether this week some professor in some politics department in France will be setting the essay “Is France becoming ungovernable?” The question, however, is not the right one.

The correct question should be “When, why and how did the central banks abrogate the responsibilities of government?”

Since the beginning of the 21st century – I find it scary that nearly a quarter of it has passed by – the real power has not rested in the parliamentary debating chambers and in the executive offices but in the monetary policy committees of our central banks.

In September 2001, it was neither President George W Bush nor New York mayor Rudy Giuliani who put the wounded nation back on the road to recovery. It was the Federal Reserve System under the leadership of Alan Greenspan that pumped cheap cash into an economy that had collectively lost its confidence. Greenspan was the hero of the hour. Seven years later, the GFC, the Global Financial Crisis, struck and while politicians of all nations and of all political colours were floundering, it was Ben Bernanke at the Fed, Jean-Claude Trichet at the ECB and Mervyn King at the Bank of England who, to quote the Corsican usurper Napoleone Buonaparte, found the crown in the gutter and picked it up.

Yes, the real power lay not in the hands of elected politicians but in those of unelected central bankers. I recall a few of the usual rumblings about unelected appointees being in charge but few would have convincingly argued that they were not making the best of a bad job. The peak of central bankers’ power was reached when Mario Draghi, successor to Monsieur Trichet, grabbed the reins during the eurozone crisis and with his legendary: “Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough.”

I cannot recommend enough reading the entire speech which he gave at the Global Investment Conference in London on July 12 2012 and which is more presidential than any presidential speech you will find since possibly JFK’s inauguration address in January 1961. Verbatim of the remarks made by Mario Draghi.

If it is “the economy, stupid”, then nobody has more sway than the central banks and for most of the century so far it is they who have been making the running. And where are they now? As hard as I listen, I cannot hear them. Have the political classes retaken control by merit or have the central bankers gently abrogated it and quietly placed the crown back in the gutter? With US stock indices describing a path redolent of one of Elon Musk’s rockets and with bitcoin now trading above US$ 100,000, do I hear Jay Powell warning of irrational exuberance? Is the Fed lining up to drain liquidity in order to protect citizens from a probable stock market bubble? It is when too many analysts and strategists at too many bulge bracket firms confidently declare that there is no bubble, and that high valuations are totally justified, that I get scared.

The joys of online trading have brought many tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of rank amateurs into the trading space. The 2021 GameStop bubble and bust on one hand demonstrated the power of private players – I shall avoid referring to them as investors – but on the other hand also demonstrated the extraordinary risk inherent in momentum traders and in FOMO (fear of missing out). Is Tesla Inc at US$ 357.93/share and a p/e ratio of 98.14 times really any better? At 57.19 times earnings NVidia is positively cheap. Only a moron would not acknowledge that there is a build-up of risk. Please don’t get me wrong. I am not forecasting that stock markets are within inches of falling over the edge, but the optimism reflected in some of the prices will be very hard to meet, and woe betide those who are naked long the go-go stocks when reality pops its head around the corner.

Markets have an uncanny habit of looking at the stats that support the direction in which they are going. Tomorrow, Friday, is a big day for economic releases with the key US payroll report following on from the eurozone’s initial estimate of Q3 GDP and my guess is that they will come and go, irrespective of the numbers, with little impact on prevailing momentum. Irrational exuberance prevails and monetary authorities show very little desire to say, let alone do anything about it.

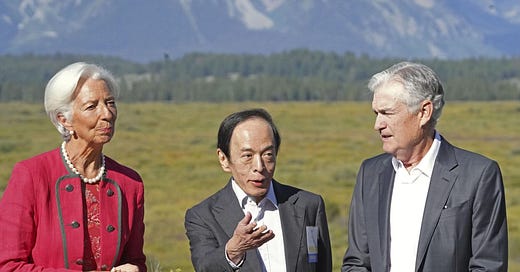

There is much talk about the incoming Trump administration being mightily short of “grown-ups”. For all his “faiblesse”, President Emmanuel Macron chose a proper grown-up to tackle France’s fiscal maze and look what they did to him. Germany is, as we know, in an equally confused political quagmire and looking around the European continent there are few countries that are not struggling for direction. And where is Christine Lagarde’s equivalent to Draghi’s “whatever it takes”?

For well over two decades the central banks were sometimes quietly, other times not so quietly, the power behind the political throne. Donald Trump looks to have scared the living daylights out of the Fed which is out of a sense of self-preservation keeping its own council and in consequence the ECB and the BoE are doing the same. As a result, risk asset markets, and I include cryptos, are having a party. It was William McChesney Martin, Fed Chairman from 1951 to 1970, who coined the phrase that the Fed “is in the position of the chaperone who ordered the punch bowl removed just when the party was really warming up.” Which he followed up with the observation: “If we fail to apply the brakes sufficiently, and in time, we shall go over the cliff.” In my book, that should have the Fed considering tightening monetary policy and not loosening it. If it does cut rates a week next Wednesday it will be confirming that it has effectively given up control and that is not something we should be celebrating.

Back to France where the yield on the 10 year OAT at 2.89% remains flat to the 10 year Greek government bond. I was intrigued to find all over the place articles titled something along the lines of “France. What happens next”. I’m glad that someone seems to know because I most certainly don’t. There is no question that Young Macron should step down although I suppose it will be up to Brigitte to do what Jill Biden apparently didn’t and to offer her husband guidance. Macron of course will fear, and not without justification, that early presidential elections will see Marine Le Pen achieve precisely what he has supposedly spent seven years trying to avoid. When in 2008 the political class handed the reins of power to the unelected monetary authorities, it also inadvertently lost the control it had once commanded over what had been touted as the democratic process.

Gaetano Mosca, Vilfredo Pareto and James Burnham would recognise the disconnect although they could of course never have predicted the power that social media would one day exert over the formation of public opinion. The old political establishment to which even Young Macron belongs is at a loss.

I’m sure that someone somewhere has opined that democracy is far too valuable to be left to the whim of the electorate.