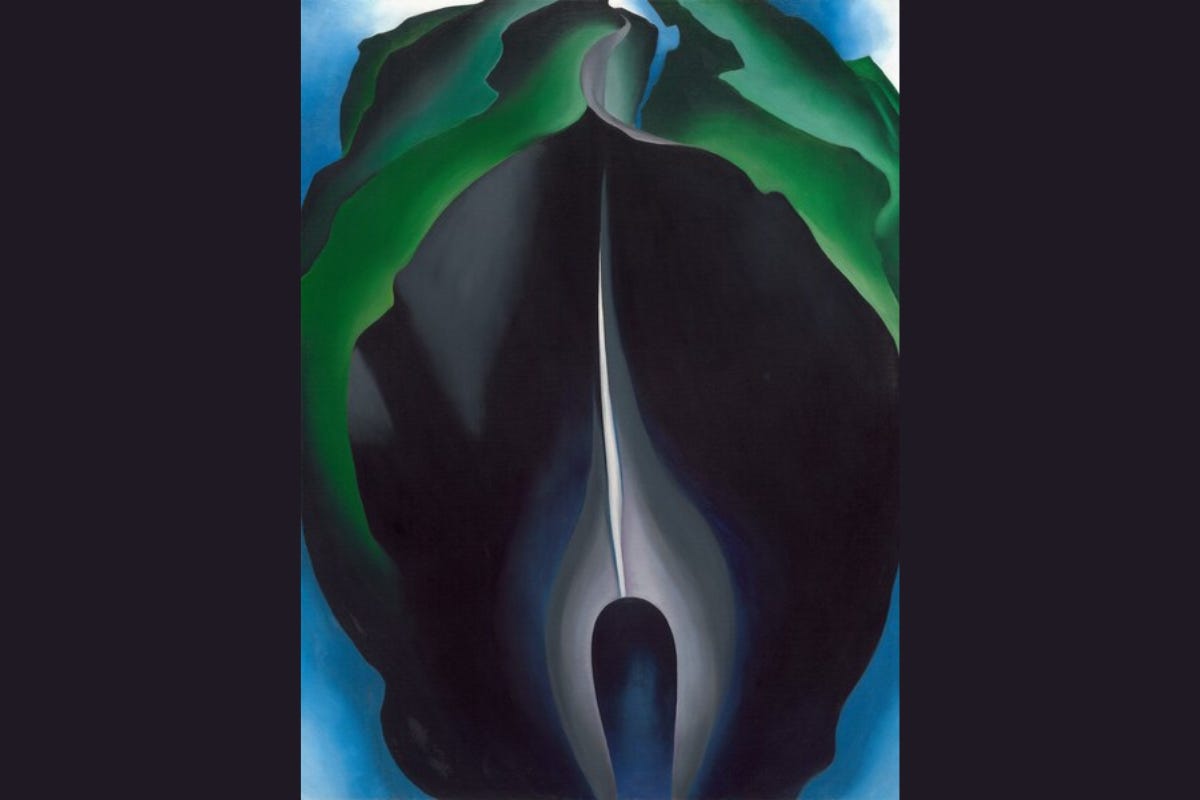

Stop and Look: Jack in the Pulpit by Georgia O’Keefe

Abstraction was an instinctive impulse for O’Keefe.

Georgia O’Keefe painted a number of studies of plants that present the organic forms of flowers as though they were landscapes – details of the American scene that have the overpowering presence of mountains and canyons. This depiction of a common wild plant in the brooding colours of a thunder storm confuses our sense of scale and makes us reimagine an intimate natural encounter as a sublime experience.

At the same time, abstracted as it is, this image of O’Keefe’s shares something of the aero-dynamic slickness that we associate with commercial design of the “Art-Deco” period in which the picture was produced and to which it firmly belongs.

It’s reassuring to know that, however inventive and independent artists are, or feel themselves to be, they cannot help being representative of their period. Indeed, it’s surely the function of an effective, fully articulate creative voice to present aspects of the character of its period in a memorable and permanent form.

The plant that is presented to us so powerfully here is a familiar American wild flower with a charming popular name, Jack-in-the-pulpit (Latin: Arisaema triphyllum), which is related to the British (and European) plant with an equally homely country name, the cuckoo pint, or lords-and-ladies. In Latin, this is Arum maculatum, a name that tells us that it belongs to the lily family. The tall vase-shaped sheath enclosing an upright seed-head often bearing bright red berries is distinctive, and readily suggests many quite different objects. O’Keefe imaginatively pursues that train of thought in her painting.

Born in the far western state of Wisconsin and trained in Chicago (later also in New York), she came to be identified with the rugged landscape of Western America and, as this picture shows, could transform even small-scale objects into monumental images.

The art dealer and renowned photographer Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) admired her work and they married in 1924, settling in his home state of New York, but she continued to be inspired by remoter regions, especially the semi-desert landscapes of New Mexico, which seem to have led inevitably to experiments with abstraction. Rather than moving towards Steiglitz’s medium of photography, O’Keefe was one of the first Americans to embark on that innovative course. As we see here, abstraction was an instinctive impulse for her and, allied to her sense of visual drama, enabled her to give expression to some of the fundamental sources of energy in American geography.