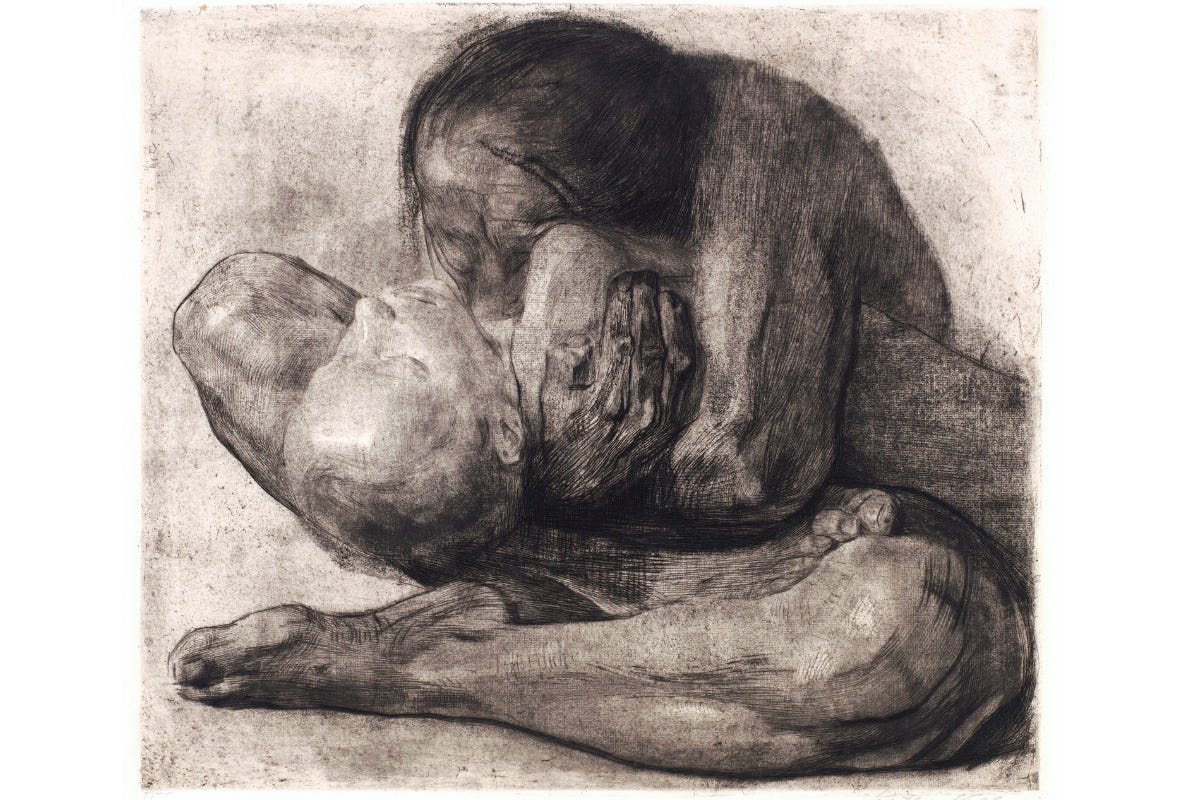

Stop and Look: Mother with Dead Child by Kollwitz

Kollwitz's subject matter was almost exclusively the human figure, often under extreme emotional stress.

There is an uncompromising, elemental violence in this image that shocks us despite its statuesque stillness, and the fact that the figures are generalised to the point of anonymity. Although it is vivid and immediate, it is not a personal likeness of an individual enduring bereavement, but a universal image of grief projected on a very grand scale which nevertheless succeeds in affecting us by the poignancy of the emotion conveyed. In this, it exemplifies Kollwitz’s remarkable achievement. Her subject matter was almost exclusively the human figure, often under extreme emotional stress. As we see here, she wasn’t confined by the print medium to working on a small scale. This etching seems to unite the intimacy of a print with the force and scale of life-size carving.

Kollwitz was born Käthe Schmidt in Königsberg, East Prussia, now Kaliningrad and part of Russia. At an early age, she was impressed by the work of Rubens, fine examples of whose large-scale figure compositions she was able to see in Munich, and by the Symbolist etchings of Max Klinger (1857-1920). It was soon evident that her primary subject matter would concern human suffering and the harshness of existence. She was to live through both World Wars and lose one of her two sons in the first.

As this image powerfully demonstrates, she had already at the start of the century plumbed the deepest horrors of experience. She worked in all the media of visual art but her most memorable work is in the form of etchings or sculpture, in both of which media she achieved exceptional grandeur and pathos. She was drawn to the gritty realism of Emile Zola’s novels, and began a set of illustrations to his famous treatment of unrest in a mining community, Germinal (1885).

In 1888, she married a doctor, Karl Kollwitz, with strong political leanings and a founder of the Social Democratic party, in which she too became actively involved. Her humanitarian concern was expressed in her lifelong engagement with left-wing politics: she became an active Socialist and in due course joined the Communist party. But the power and sincerity of her work have a relevance that is far from being wholly political and her prints were admired and collected throughout her lifetime in both England and the United States as well as Germany and elsewhere in Europe.

Kollwitz is often grouped with the German Expressionists, with whom she has much in common. But there is a searing honesty in her depictions of human suffering that makes the distortions and bright colours of the Expressionists seem self-conscious, mannered and almost artificial. She deserves an honourable position of her own in the art of a terrible epoch.