Street Scene: Frost Opera Orchestra delivered the power and punch Weill intended

Kurt Weill’s timeless 1947 opera was a smart choice for a music school production.

Frost in Florida? After hurricanes, folk in Miami seemed battened down for anything. But scrub global warming oxymoronic headlines – ‘Global Warming Brings Big Freeze to Sunbelt State’ sort of thing – for now.

This isn’t a weather warning. It’s opera from Miami’s Frost School of Music. Street Scene, Kurt Weill’s 1947 opera about a day in the life of New York tenement dwellers over two sweltering days during a torrid Big Apple summer.

Smart choice for a music school production, not least because it involves 32 characters, walk-on-by supernumeraries, and a children’s chorus. Five per cent of the student cohort of 700 are onstage. Another five per cent are in the orchestra pit. Even more are backstage. The rest seemed to be in the audience.

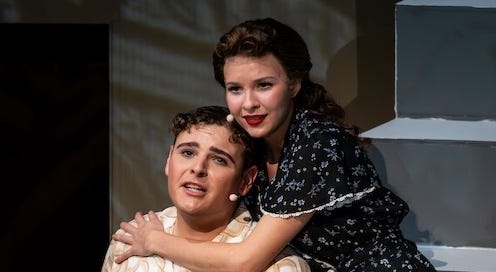

Often music school productions can be uneven. That’s a charitable way of saying appreciated by cooing mums, dads and siblings only. Frost’s Street Scene was slick, packed with soaring, youthful voices, driven by meticulous direction.

Available as a live stream, it is well worth squirrelling away some mince pies, as I did, putting on those Christmas noise-cancelling headphones, waving knowingly from time to time at chatting relations and diving into one of Weill’s most compelling dramas.

Here’s a brief synopsis. Act I.

Outside 346 Lower East Side, in 1940s New York, neighbours trade local gossip, complaining about the unbearable heat, annoying mozzies.

Frost’s staging was simple, with clever use of space, requiring no scene changes, so the drama flowed, and the audience was hooked. Broad steps led from the apartment building to a street, marked by that essential Manhattan street icon, the red fire hydrant.

The hot topic is that Anna Maurrant, Frank’s wife and Rose’s mum, has fallen into that soap opera trap. She’s having an obvious affair with the milkman. The women’s excited chatter suddenly stops when the subject of their gossip appears.

Different plotlines emerge as characters embark on “setting” arias. Daniel Buchanan, uneasy about his wife’s imminent childbirth; Abraham Kaplan, a Jew whose anti-capitalist harangues entertain some and exasperate others.

A youthful Jenny Hildebrand, from a German family, radiant after graduating from high school; Italian Lippo Fiorentino, who hands out ice creams to everyone; janitor Henry Davis, who lives in the building’s basement; Mrs. Olsen, prepared to leave her baby, preferring to spy on the neighbours; and a couple returning from a night on the town.

Every singer is provided with a catchy character-defining aria by Weill. The stage director made sure each had their place in the sun as they told their tales. The audience was quickly immersed in the plot, up to speed with the gossip.

Focus of the action is Rose Maurrant, the daughter of Anna and stagehand Frank. He’s a tough guy, hard drinker, severe and reactionary. There is little audience surprise that Anna prefers that extra pint of milk.

Rose is a young, decent clerk in a real estate agency, besieged on many fronts. Rumours about her mother’s adultery, also because she is haunted by two creepy seducers. Her neighbour Vincent, a hustler always ready to pick a fight, and Harry Easter, her predatory boss who tries to lure her into an adulterous affair with promises of a career in show business.

The counterpoint is second principal character, Sam, the Kaplans’ son, a law student with all the diffidence his gobby-mouthed father lacks. Sam loves Rose deeply and repeatedly suggests instead of returning his library books, they should flee to start a new life far away from the slum.

ACT II

Having set the scene deftly, Weill turns to storyline development. Life goes on. Children mimic stock New York characters in their games, the neighbours celebrate Daniel Buchanan’s newborn child, and the bailiffs evict the Hildebrands, abandoned by the father and unable to pay the rent.

One of the ongoing snippets of everyday life has an ominous potential: Frank Maurrant tells his wife Anna he has to go downtown. Rose is away at her boss’ funeral. The coast is clear for a milk delivery.

Anna invites her milkman upstairs. The inevitable happens. Frank’s back! He climbs the stairs to the apartment. In flagrante! Two shots ring out. The milkman dies on the spot, Anna is taken away by ambulance. Frank escapes in the confusion.

Shortly afterwards, the street has won. Life goes on as if nothing had happened. Nannies spend the afternoon snooping, pushing their prams past the spot that appeared in the newspapers. They gossip about their moment in the headlines.

Rose returns from the hospital where her mother died and finds solace in Sam, who says again, “nothing to stay for, lets run away”. This is the pivot point of the opera. She rejects him because she says she doesn’t want to be a burden and force him to abandon his studies.

Miami’s version makes it clear she is just unprepared to make the commitment. Some of sleazy Harry Easter’s showbiz mirages are still swirling in her head.

The police track down murderer Frank. Before taking him away, Frank tells his daughter, pathetically, that he loved her mother but couldn’t control himself.

Everything returns to a closing scene of banal normality. New tenants waving brochures move into the Hildebrand’s apartment. The neighbours chat about the stifling heat, the annoying mosquitoes and the local gossip. We await another chapter of life in the street that has changed so many lives.

Weill’s score is fabulous. Powerful lyricism without a platitudinous line or wasted moment anywhere. Frost Opera Orchestra did a magnificent job delivering the power and punch Weill intended. The voices were remarkable. Direction of the complex action admirably slick.

Weill wrote thirteen operas. I have seen only The Threepenny Opera and Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny before encountering Street Scene at Frost. For some reason, his output is regarded as “difficult”.

Confrontational, in your face, yes. But Weill tells his stories, whether a rewrite of John Gay’s 18th century story ballads of the poor, Bertold Brecht’s alarmingly prescient reflection on Germany’s corrupt 1920s political culture, or late 1940s New York, with consummate clarity.

They are timeless stories. In Street Scene when the wheel turns the audience realises that outside the theatre, the world we will find as we jostle our ways home will be much like the condensed version we have seen onstage.

I had the privilege of meeting Shelton G Berg, (Shelley), Dean of the Frost School, for breakfast. Round an intimate table in a Coconut Grove home, looking out on the bay.

I have never before been in a family home with two original Andy Warhol silkscreen “Marilyn Monroe” style images – of the lady of the house on the wall. The remainder of my host’s art collection was to a similar standard. A different world.

En route from Miami to Coconut Grove the landscape shifts from high rise bustle to a road shading canopy of gumbo-limbo, swamp laurel oak, banyan, mahogany, coconut palm, fig, mango, and bullet trees. Maybe Humphrey Bogart and his small-man Colt 903, en route to Key Largo, lurks in the background with Lauren Bacall.

A visit to the Frost campus – a delightful, open space with a spanking new lakeside auditorium – is followed by an evening at Winter Wonderful, a glitzy dinner and concert in the JW Marriott Marquis Hotel, central Miami.

A cocktail reception graced by fairy-clad stilt walkers – no they weren’t handing round the canapes - was heralded by Frost Herald Trumpets, Frost Holiday Carolers and a Frost Winter Jazz Combo. A theme emerges.

So, I should probably not have been surprised when I was introduced to Mr Frost himself. Phillip Frost M.D., a highly successful businessman. It was a timely reminder that so much of the American world of education and art rests on the shoulders of individual philanthropy.

As I recalled the recent, fortunately failed, Arts England Council attempt to castrate English National Opera on a whim, I reflected that arts organisations were probably more secure with the enduring commitment of actively engaged donors, like Frost.

The Frost School of Music under Berg’s savvy direction is able to offer its students something different. As a highly accomplished jazz musician Berg is under no illusion how difficult shaping a career will be for the 700 talents in his annual care.

So, unlike other music schools, Frost does not confine the education process to performance. In a crowded international market, there will be no guaranteed career for 700 prima donnas, heroic tenors, or cadenza-firework violinists.

Each student will leave Miami with a skillset rooted in not only performance but also the grunt of the backstage business of delivering a complete musical product.

This is supplemented by a MusicReach program aimed at opening doors for the underprivileged. An astonishing 94% of Frost graduates are immediately employed post-graduation. Only 88% of New York’s Juilliard School graduates have found jobs after six years.

Glitz, glamour, dinner interspersed with instrumental and Christmas choral delights. And a surprise. “Mr Malone, may I introduce you to Governor Jeb Bush.” The 43rd Governor of Florida was still following his dad, President George H.W. Bush’s mantra: “I may be a quiet man, but I hear the quiet people”.

Blasted by the Trump campaign in 2016, there was Jeb, still seated at the Patrons’ Table, quietly supporting the Frost cause. We exchanged non-partisan banalities, then he said, surprisingly, of my short tenure as a Minister of State in the 1990’s, “We’re an ocean apart, but from the same side of the aisle. I honor you for your service.”

As the man who might have been President walked back to his table, I reflected that was the first time anyone had. They do things differently in Florida. A street scene in Miami. Someone should write an opera.