When the Wall came down in 1989, I was living in Berlin. Whilst most people headed west, I went east, for me an unexplored world. There was beauty to be found in the landscape of nearby Brandenburg, original and surprisingly undamaged. Many of the pathways through local woodlands described by the 19th century German writer Theodore Fontane were still accessible. With German friends, I followed those same routes and was enchanted by them.

However, the main cities across what quickly became the new Laender or administrative divisions of Eastern Germany were quite another matter entirely. Old scars left from the Second World War were matched by newly self-inflicted ones. I recall visiting Magdeburg with its cathedral quite deliberately abutted by ugly new sets of flats. I journeyed down bumpy autobahns battling stinking fumes from slow moving Trabant (or Trabi) cars as I headed north to Rostock or south to Dresden. Evidence of the awful impact of the bombing of Dresden in 1944 could still be seen; and 50 years of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) had cloaked the city in a brown-coloured veneer, as if it were waiting to be cleaned up.

As Chancellor Helmut Kohl steered the process of Germans “coming-together” after the Wall had been breached, there was little doubt that it was a triumph for West Germany, but for East Germany it was a type of surrender. The “Wessies” knew this and the “Ossies” resented it, not because they thought their “system” deserved applause but as a matter of offended dignity. Even today opinion polls show that Germans in the eastern Laender still feel second-class citizens in their own country. It is not an accident that voters in that part of Germany are the most likely to opt for far-left or far-right political parties.

Katja Hoyer’s “Beyond the Wall: East Germany 1949-1990” is an attempt to restore a degree of dignity to histories of East Germany and portrayals of its citizens. Though now a researcher in London, Hoyer writes from the perspective of someone born and brought up in the GDR who studied at the University of Jena. She weaves her account of the establishment and evolution of the GDR with great skill, drawing on a wide range of sources including many individual interviews. Hoyer is not glassy-eyed or nostalgic about the GDR and the (many) villains of the piece – not least Erich Mielke the mastermind of the Stasi intelligence service for over thirty years – are targeted sharply and rightly. But she evidently seeks a just account, one which recognises that for many of its citizens the GDR was ‘home’ and valued as such. It was, she argues, a country which for all its failings and cruelties formed them as individuals and as families. Though its material comforts were inferior to those available on the other side of the Wall, it had more colour and arguably more equal opportunities than most depictions of it have allowed.

Of course as Hoyer shows all too clearly, the East drew the shortest German straw in 1945. After the implosion of the Nazi state they were landed with the Russians and a vengeful Stalin intent on milking the Soviet Zone of Germany through substantial reparation payments which dramatically slowed economic growth for decades. In large measure East Germany became a geopolitical pawn searching for a place on the European chess board. As East-West relations hardened into the Cold War the restoration of one German state seemed an ever more distant possibility. With few natural resources other than environmentally disastrous ‘brown’ coal, the GDR created out of the Soviet Zone of Germany remained dependent on increasingly expensive Russian oil supplies, especially after the mid-1970s.

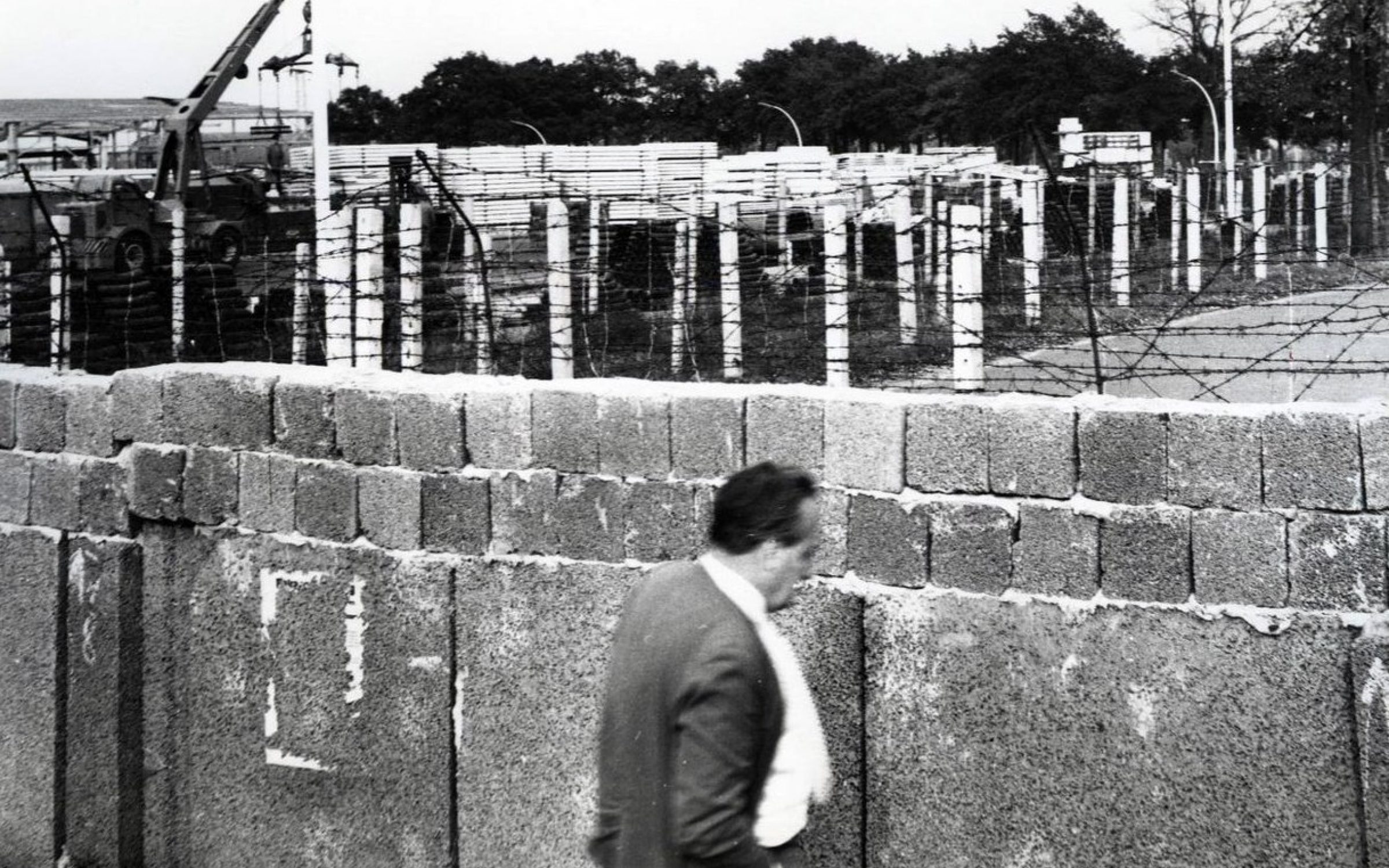

East German government leaders, not least General Secretary Walter Ulbricht, were shaped by Soviet communism and practised repressive skills they had witnessed whilst in the Soviet Union before and during the war years. As Hoyer demonstrates, the 1953 uprisings in East Berlin and other cities were suppressed by Ulbricht and Co without mercy and left the leadership uneasy for many years thereafter. Control became the watchword of the GDR. Indeed it was an uncontrollable exodus of highly qualified citizens in the late 1950s which directly led to the construction in haste of the Wall across the whole country in 1961. Dozens thereafter died tragically in their efforts to escape across the border; but Hoyer tentatively suggests that the Wall induced a certain stability and a growing if reluctant acceptance of the GDR by its own citizens.

Nor were Ulbricht and his successor from 1971, Erich Honecker, unmindful of the need to craft an economy and society which met at least some of the aspirations of their fellow East Germans. The communist leadership was often surprisingly pragmatic in pursuit of such objectives. Access to higher education for children from working class families was better in the GDR than in West Germany. Women had greater employment opportunities than their equivalents in West Germany because of the provision of universal child care in the GDR. Flats and houses may have been inferior to those in West Germany but they were available and affordable. Hoyer also cites in amusing detail less serious examples of the leadership responding to public demand such as the importing at great expense of Blue Jeans from the US.

The needs of young people and successor generations were a growing preoccupation of the leadership and one of those young people was Angela Merkel, the future Chancellor of a unified Germany. As support for her contention that the GDR was not all black and white repression and stunted opportunities, Hoyer relates how at her farewell ceremony in Berlin in late 2021, Merkel asked the Bundeswehr’s musicians to play Nina Hagen’s famous song ‘Du hast den Farbfilm vergessen’ (‘You Forgot the Colour Film’). She listened with tears in her eyes, the song serving as a reminder that life in the GDR wasn’t all bleak.

What Hoyer has done in “Beyond the Wall” is to provide a rounded account of East Germany’s distinctive history. Her book is never saccharine or sentimental and she never implies that the Wall was other than an abomination. But she shows the GDR as another part of post-war Germany, one just as ’real’ as its western counterpart and worthy of as fair and balanced a portrayal as possible.

Write to us with your comments to be considered for publication at letters@reaction.life