The horror of 6 January at the Capitol has been eased to some degree by the uplifting elements of Joe Biden’s inauguration as the 46th President of the US last week. Many of us abroad must have responded warmly not only to the resilience displayed by the ceremony in the face of Covid and the events of a fortnight before, but also to the President’s heartfelt calls for unity and a remarkable and inspirational poem reminding us all of what America is and can be again.

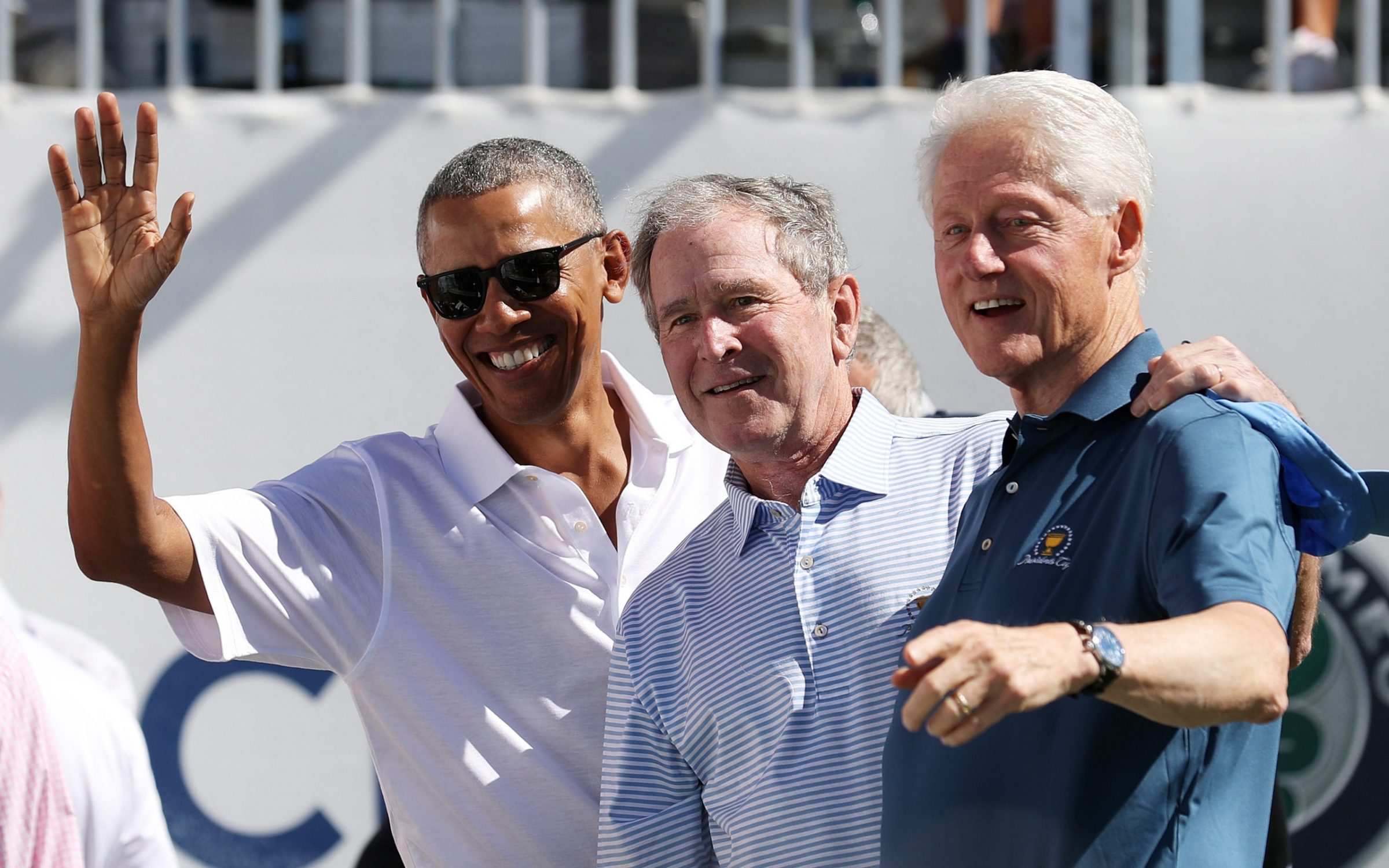

Something else caught my eye. The presence of previous presidents is a feature of Inauguration Day, a manifestation, as Biden remarked, of “cause over candidate”, the importance of which in present circumstances was magnified by the petty, but welcome, absence of Donald Trump. However, it was the video which went viral of presidents Bush, Obama and Clinton, evidently at ease with each other, talking of unity and how to deal with difference, which struck another chord. It prompted some here to try to imagine previous Prime Ministers doing the same, whether or not it was possible, and if so, around what would they coalesce?

I am an unashamed believer that consensus in politics is as important as confrontation, and have been so all through my Parliamentary and Ministerial career. They both have their place, but I don’t buy the macho argument that consensus implies a weakness, though I’ve been perfectly willing to stand my ground and risk career when needed. I am increasingly doing so, as recent years have added to the polarisation throughout liberal democracies, seen most obviously in the US, but experienced here with the pain of the bitter Brexit campaign, the shock of the death of Jo Cox, and the increasingly nasty undercurrents emerging from social media.

Our system rightly emphasises choice for the electorate, and it would be a naïve Pollyanna who would ask parties constantly to “go high” in response to those that “go low” as the public’s support is sought – no one has clean hands here. But extreme shocks to the system demand responses, and I think we are flexible enough in the UK to judge when we should respond outside the box.

I would welcome, therefore, firstly a public platform where former prime ministers of different parties discussed what they, and the people of the UK, had in common as well as where they legitimately differed. Our democratic process relentlessly exposes the latter, but we never make anything of, for example, agreement on the rule of law, the peaceful transition of power, the need for an honest democracy, or the requirement for objective truth on which people might base decisions. This leaves a growing number of citizens questioning whether there is anything collective in the UK that we believe in. This is no longer any academic debate, nor can we take basics for granted anymore. I think we might be in danger of forgetting, or worse, being persuaded against, that there is anything in which we all believe. As in the US, there are many who now see no “mainstream” news, nor local news; who disbelieve facts and “experts”; who absorb lies as truth and have no markers for what truth might be anyway.

When life is fine and dandy for the UK and its people, this might be all very well. But at present we are confronting this when a pandemic is also eating away at the very pillars of life, of human contact, of family, work, education, and which at present has no end date, and will affect and impoverish us for years to come. Passing the grim and almost unbelievable milestone of 100,000 deaths, our society has reached a situation none of us could have imagined a year ago. But our political process is handling this as we do debates on road traffic and planning – Government, Opposition and media talk to themselves and scrap away fruitlessly in front of an increasingly sceptical public, whether it is about the present or, much more rarely, the future. While every other sector has taken the pandemic crisis as an opportunity to examine ruthlessly their delivery, we are still doing pre-crisis politics.

Enough. It is blindingly obvious that life will not be the same in Britain after the pandemic, and we are tinkering around at the edges. So, secondly, I would like to see the current government establishing a series of commissions – politically broad, not HMG-led – to examine where we go from here. One of the great successes of 1939-45 was the ability of that non-partisan Government to look ahead in the midst of war, to what should emerge from peace, evidenced by the Beveridge Commission on Welfare, or the collective efforts that created RAB Butlers Education Act of 1944. We could do the same. It could be finding the answer to the issue of social care and its funding which successive governments have failed to solve; constitutional change examining a Britain post-Brexit; the green revolution needed to combat climate change, or even an agreed economic road map as we work out how to pay for the rescue which the present Government has been delivering while it rips up previous Tory economics. The link between them, being honest, is that these issues will outlast the present Government. The public know two things which political parties never publicly acknowledge or prepare for – that the party will sooner or later be out of power, but also that many policies endure electoral change and are privately shared or tolerated by other parties that have no intent to reverse them.

A confident government and Prime Minister now would bring in others. Not as a national government – the time has not come for that. But to advance unity in the face of crisis, and be ahead of the curve. There should be a greater role for Select Committees – they are cross party and are one part of Westminster which have earned respect. Importantly, cutting out Parliament altogether with bodies such as People’s Assemblies risks fitting the agenda of those who wish to create a bigger gap between Parliament and the People – the sort who stormed “the people’s House” the other week, having fallen prey to the lie that their system was corrupted.

In the midst of this pandemic, in the face of the shock to democracy that we have recently witnessed, our politics should seize the opportunity for something different. I think plenty are waiting to give it a go.

Alistair Burt was the Member of Parliament for North East Bedfordshire from 2001 until 2019.