What is the single biggest barrier to the UK achieving net zero carbon by the year it has set for itself, 2050? The answer has to be the Treasury’s antediluvian approach to nuclear power. The government estimates of future electricity demand are far too low; by 2050, we will need at least five times the electricity we use now as fossil fuels cease to be used. So, how will we produce this energy?

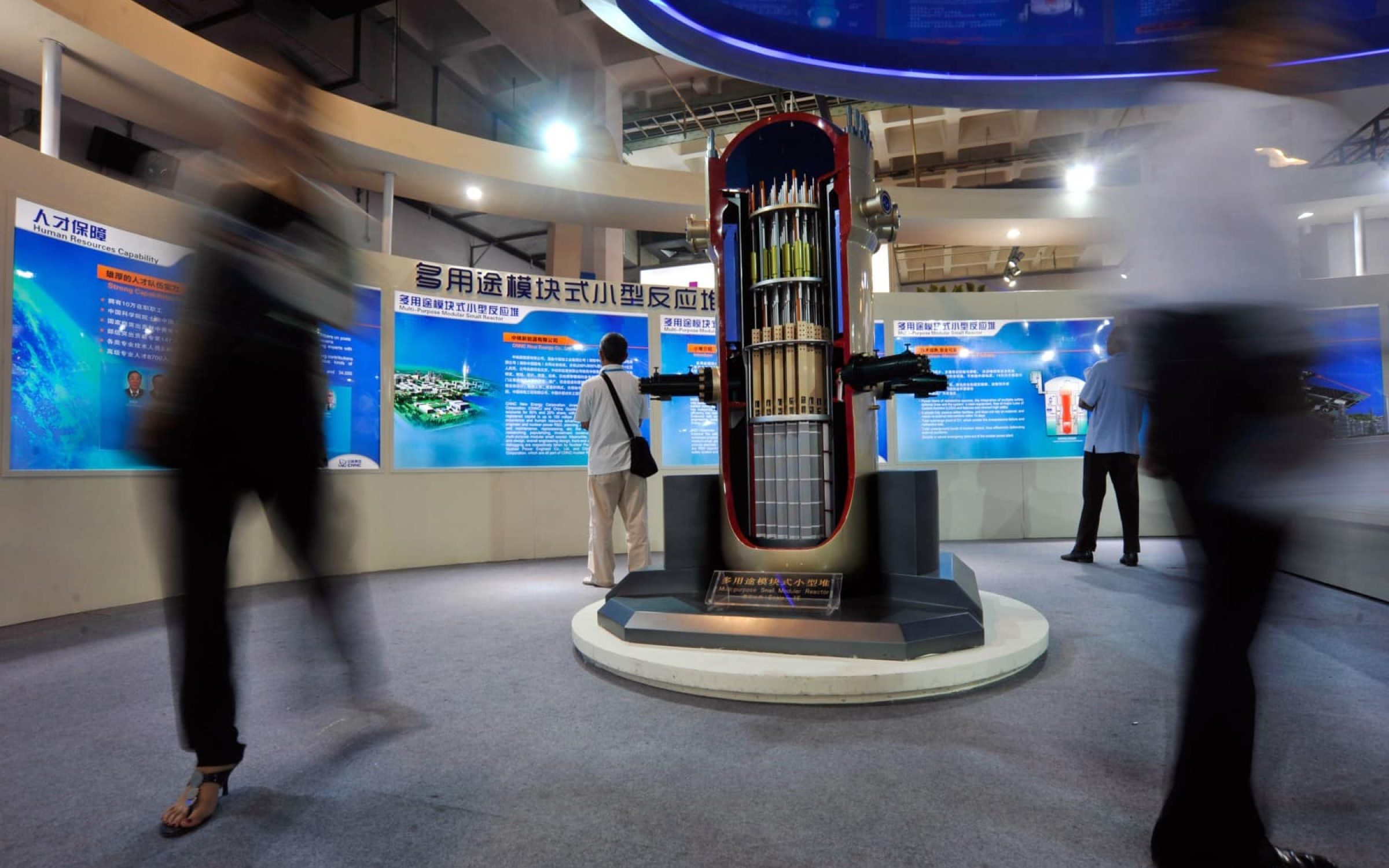

Renewable electricity generation is intermittent; the wind does not always blow (enough) nor does the sun always shine (especially not at night). Hydrogen and batteries can supply short-term storage capacity but not enough; both consume more electricity than they can supply. Fossil fuels will require carbon capture and storage, as yet untested at scale and the fossil fuel producers are reluctant to pay the unknown costs. This only leaves nuclear to provide backup. Specifically, the new generation of small modular reactors (SMRs) can modify supply (ramp up and down) to meet demand variations.

Could nuclear power really be the answer? No doubt, there are issues. Hinkley Point C, with its massive delays and financial overruns, has given financing nuclear a bad name with private sector and local authority investors. The government is, nonetheless, fixated on trying to repeat this model for another nuclear power station in Suffolk, Sizewell C. As the Financial Times has reported, local authorities are refusing to agree with the Chancellor for many good reasons: the length of the planning process, the uncertainty of final costs, uncertainty about future price of electricity generated by nuclear and profits and complex and changing regulation.

It is fair for investors, both private and local authorities, to be wary of behemoths like Hinkley Point C and Sizewell. But the Treasury’s thinking is outdated: it must recognise that the behemoths are being overtaken worldwide by the flood of SMRs where the rules are, or should be, quite different.

The large number of SMRs required by the UK market means that we can have a competitive clean energy market as SMRs compete with renewables. The government should not need to interfere beyond providing financial assistance for the energy-impoverished through welfare services. It should not affect electricity generators or how clean electricity is generated.

Streamlining planning and regulation is the key to solving the Treasury’s financial infrastructure problems. There are three main areas of consideration for rolling out SMRs: the SMR plants themselves, the sites where they should be located and the planning regime.

On the hardware side, the UK Office for Nuclear Regulation is, commendably, working more closely with its international counterparts and moving towards shared testing and approval processes. But they have a long way to go to become as speedy and effective as they need to be. This means that UK approval of the SMRs can simply rubber stamp what has already been approved elsewhere. The planning process could instead take a few weeks rather than years.

Sites are more difficult as environmental issues are essentially national and somewhat devolved. The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, other government bodies and consumer lobby groups share many of the same outdated views of nuclear as the Treasury. The government needs to educate itself, and then the public, about the size, scale, safety and reliability of SMRs. Climate change is not simply a global matter but has impacts nationally and locally. The Environment Agency, and its national and local associates, need to become more cognisant of the benefits of SMRs.

Because of the multitude of bodies involved, consultation should be in parallel, not in series. First, Great British Nuclear (GBN), not the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, should list potential sites (with SMR sizes and numbers for each) and invite those bodies that wish to be consulted to register. These site listings should be based on consultations with SMR suppliers promoting the benefits of the hardware envisioned. Registrants should each have to specify any additional data they need in order to reach their recommendations within two months of receiving that information.

The GBN briefing to registrants should stress the advantages of agreement. Registrants would be free to pitch for modest financial or other inducements but bear in mind that the allocation of sites will be competitive: those demanding more ambitious incentives will be less likely to get them.

Finally, as is widely recognised, planning needs to be brought under control as it is in France. When Hinkley Point C was first mooted, 40 or so requirements were set out. Today, the equivalent Sizewell C is faced by over 2,000. These result from a fear of judicial review which adds delay, cost and complexity, and denies the country the electrification we so badly need. Judges should be taken out of the picture and the proposals from registrants subject to just one level of review.

In other words, SMRs are the future of British energy and the sooner the Treasury and consequently the public realise this the better. We must relax planning processes, assure investors and work closely with other countries to speed up the whole process.

Write to us with your comments to be considered for publication at letters@reaction.life