In the summer of 1988, more than 30,000 Iranian political prisoners were executed in the jails of Ayatollah Khomeini and the young Islamic Republic. Now, a justice movement is campaigning for the perpetrators to be tried in court.

Those responsible for the executions are the stars of Iranian politics today. Neither the current government nor the opposition have managed to distance themselves from the 1980s, a “crucial” decade in which the Islamic Republic solidified its rule over the country. It is akin to historical episodes which still haunt the memory of modern European countries, such as the terrible fratricide of the Spanish Civil War.

So, what is so “crucial” about those times and why are they once again in the news spotlight in Iran and elsewhere?

In its report on Iran, published on August 2 2020, Amnesty International said: “human rights defenders seeking truth, justice and reparations for thousands of prisoners who were summarily executed or forcibly disappeared in the 1980s are facing new kinds of reprisals from the authorities. This group includes the victims’ relatives, who have become human rights defenders out of necessity, and young human rights activists who have seized social networks and other platforms to discuss past atrocities”.

The NGO continues: “The new crackdown has rekindled calls for an investigation into the murder of several thousand political prisoners in a wave of extrajudicial executions in the country in the summer of 1988”.

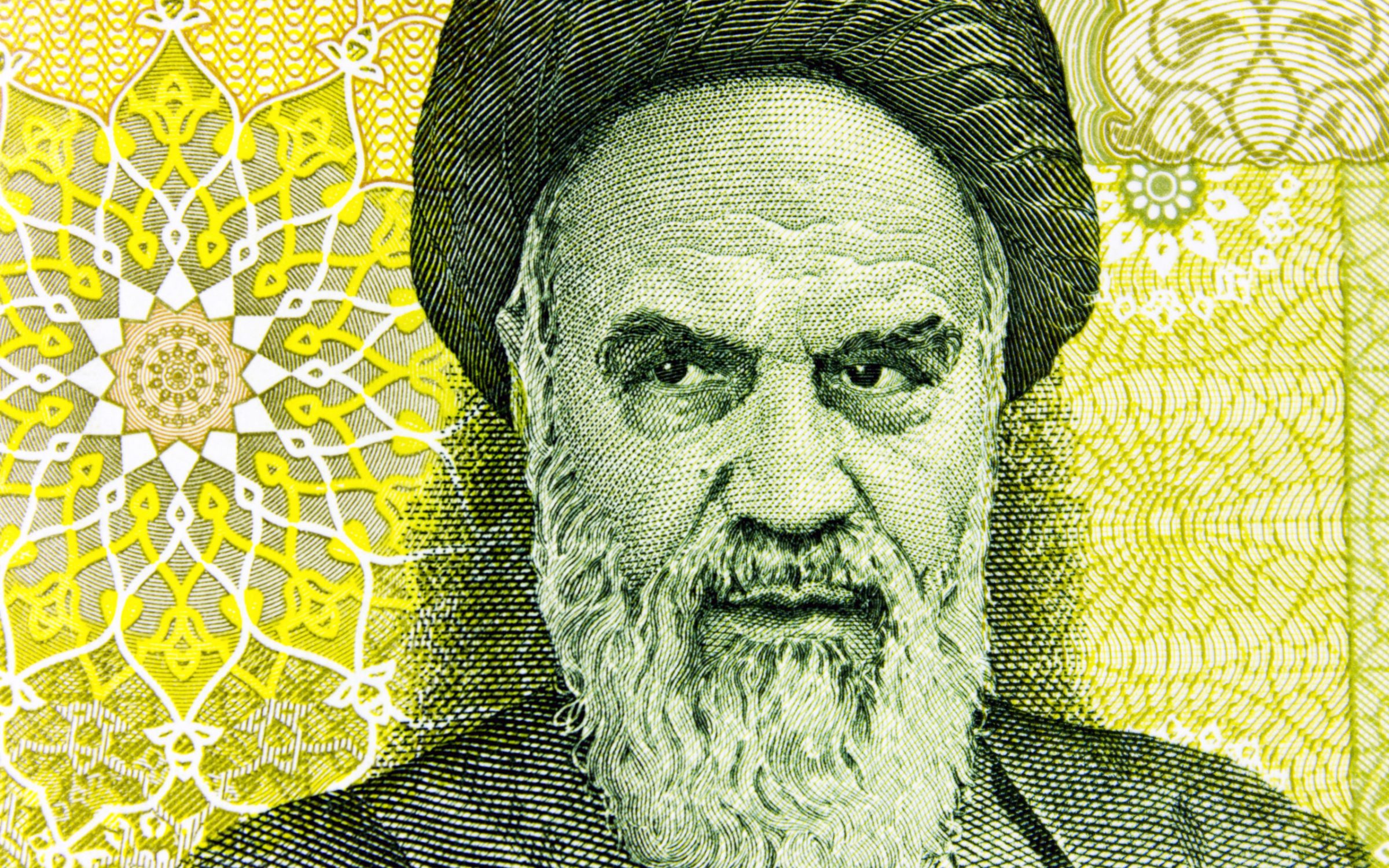

Let’s go back to those early years of the Islamic Republic. Ayatollah Khomeini, who, on his arrival in Paris in 1978 had sworn in an interview with Le Monde that he would retire from power to continue his studies in Qom, was now unrecognisable. On his return to Iran in February 1979, he quickly forgot about his theological studies, and eventually dismissed his overly liberal Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan a few months later.

The first dissent to his personal rule arose when he imposed on the Constitution of the new Islamic Republic the principle of Velayat e-faqih, or “the guardianship of the jurist”. This cemented the power of a religious leader at the top of Iran’s political system – an arrangement which is still in place today.

By then, Khomeini had already been implicated in the bloody repression Iran’s Kurdish and Turkmen minorities. As for women, the agenda was epitomised by the crude maxim, “the veil on the head or a blow”. They had already been removed from many key positions in public administration. As if all that was not enough, the first parliamentary and presidential elections in the spring of 1980 were undermined by widespread fraud which left no room for opposition parties (not a single seat in the Assembly).

As for the early foreign policy of the new regime, it had already become defined by two big events of international importance: the hostage-taking of the American Embassy in Tehran (from November 4, 1979, to January 20, 1981) and the war against Iraq that began on September 22, 1980, which was considered by the Ayatollah as “a divine gift”. He sent thousands of Iran’s young men to die on the battlefields of that terrible conflict.

When the year 1981 began, most of the opposition movements had been silenced. Only one of them still managed to gather the crowds and challenge the regime’s terror: The People’s Mujahideen (PMOI/MEK). Almost 50 militants from this group had been murdered by the henchmen of the new authorities. However, this would not prevent them from launching renewed calls for a peaceful demonstration, to demand the release of those whom the new regime had sent to its fledging political prisons.

On June 20, 500,000 people took the streets of Tehran in protest. The regime responded by opening fire. Hundreds of protesters were killed on the spot, before raids began throughout the country. Before long the prisons were overflowing with political opponents, shot in groups of “400 a night”, as some of the survivors told later. Adults, young, old, women, no one was spared. In the list of murdered people drawn up by the opposition, there were even 13-year-old girls.

For someone to end up murdered, “it had been enough to sympathise with the movement”, the former head of the secret services, Mullah Ali Fallahian, stated in a recent interview about the events of the 1980s.

In 1988, Khomeini’s war machine was out of breath. “No one was fighting at the front”, said General Said Ghassemi, one of the military commanders at the time (after repeating for eight years that he would continue the war against Iraq “to the last stone in the capital”). Yet without a war to justify everything, from poverty to the assassination of the opponents, the theocracy could not avoid a social explosion.

It was at that moment that the Supreme Leader issued a fatwa to put an end to all remaining opponents in Iran’s prisons, even those serving sentences handed down by the mullahs’ courts. The logic was simple: any outburst of popular frustration can be controllable so long as there is no coherent opposition to lead it. This logic led the execution of more than 30,000 political prisoners, most of them activists of the People’s Mujahideen. In a few weeks during the summer of 1988, they were massacred and buried in mass graves.

Hossein Montazeri, who at that time was Khomeini’s designated successor, later admitted that among the victims there were pregnant women and teenagers. This was a true massacre that affected many families in Iran, but none were allowed to mourn. Instead, a tragic silence fell on the country for many years afterwards.

Yet the movement to demand justice has now quickly spread throughout Iran, mobilising in particular all the families who had lost some of their members. In August 2016, an audio recording of a meeting held in 1988, where leaders discussed and defended the details of their plans to carry out mass executions, was released. Amnesty International explained: “The release of the document triggered an unprecedented chain of reactions from leaders who had to admit for the first time that collective executions in 1988 were planned at the highest levels of government”.

Many young people, who were unaware of this page in Iran’s history now also joined the movement. Quickly, it took the form of a call for the dictatorship’s leaders to respond to justice, and the rediscovery of the regime’s brutal repression in the 1980s came to a head in the 2017 presidential election. Ali Khamenei, now Supreme Leader of the regime in Tehran, had planned to manipulate the 2017 contest in order to make one of his closest collaborators, Mullah Ebrahim Raisi, the president of the Republic. The Supreme Leader’s great mistake was to underestimate the extent to which the movement for justice was already spreading throughout the country.

Raisi was one of the main characters of the 1988 massacre. As a member of the Tehran commission, later called the “death committee” by the families of its victims, he was appointed by Khomeini to ensure that the fatwa against political opponents was “properly” carried out in the city’s prisons. Three decades later, his candidacy provoked a real outcry among the population. Both on the walls of the street and on social networks Iranians declared: “Neither the executioner nor the charlatan”. The executioner was Raisi; the charlatan was Hassan Rouhani, the incumbent president, who was eventually re-elected on May 19, 2017.

Khamenei’s second big mistake was not to understand that this slogan symbolised the voices of Iranians frustrated with the regime bursting into the contest. It was a moment when the carefully-staged showdown between the hardliner Raisi and the moderate Rouhani erupted into an opportunity for Iranians to express their anger and grief at the massacres of the past.

“The Iranian people don’t want those who, for the past 38 years – since the revolution in 1979 – have only known how to hang opponents and put people in prison”, Rouhani said on May 7 2017 at an election rally in the northwestern city of Oroumieh. It was an extraordinary moment – an elected president of the Islamic Republic was acknowledging the massacres of the regime’s political prisoners.

Ironically, the sinister Minister of Justice in Rouhani’s first government, Mostapha Pourmohammadi, was also implicated in these mass executions. He even congratulated himself for “having carried out God’s order” in 1988 to preserve the regime. And, of course, the opposition movement did not fail to remind Rouhani that he himself has held key positions in the regime for the past 37 years. He himself is not an entirely innocent bystander.

Rouhani’s move, of course, had its own political motive. The Iranian regime has a history of manipulating elections to obtain outcomes favourable its preferred candidates. In 2009, the hardliner Mahmoud Ahmedinejad won a landslide victory over the reformist Mir-Hossein Mousavi against the expectations of many across the country. The result was a win for the regime, but only after weeks of popular protests known as the “Green Movement” were eventually crushed by security forces.

By playing on popular anger and the legacy of the 1980s, Rouhani wanted to remind the Supreme Leader that there would be consequences if he were to be brushed aside in such a manipulated election. It was a warning shot to Ayatollah Khamenei that if he were to push Rouhani aside and game the contest in favour of Rais, the incumbent president would not go quietly. They would risk a re-run of the 2009 fiasco.

As for the popular movement itself, it continued to gain momentum during the campaign as the slogans against Raisi multiplied and were amplified: “The killer of 1988” began to go viral both in the capital of Tehran and in big regional cities.

Khamenei eventually perceived that he had underestimated this movement demanding justice. He then tried to turn the tide in his favour with a speech on the anniversary of the death of his predecessor, Ayatollah Khomeini, on June 4 2017. “The 1980s were crucial times in the history of the Islamic Republic”, said Khamenei. Yet he still justified the massacres by saying that the regime would have been overthrown if his predecessor, Khomeini, had not acted in such a cruel manner.

Demonising the opposition to justify the repression of the 1980s has become a trope of official propaganda. It ranges from a whole filmography which tries to justify the 1988 massacre, to the interventions of a number of dignitaries and imams during Friday prayers across the country, who echo the regime’s line. “All those who killed the People’s Mujahideen under the order of Imam Khomeini should be decorated”, said Ahmed Khatami, a member of the Council of Experts – a deliberative body of the Islamic Republic – and a close collaborator of Khamenei’s, on July 21 2020.

Yet, for all this war of words, the regime is unable to move out from under the shadow of the victims. The perpetrators of this terror remain everywhere among its ranks. In his new government, Rouhani dismissed Pourmohammadi – only to replaced him with Alireza Ava’i, another commissioner involved in the 1988 massacres in Khuzestan province. So the bitter cycle continues, and the descendants of those who lost their lives continue to grieve without justice.

In this context, calls for the UN to investigate and bring those responsible for the killings to justice are growing in strength both in Iran and abroad. A series of exhibitions to mark the anniversary of the massacre was organised in Paris this summer (August 16-17 at the first arrondissement town hall and August 30-31 at the second arrondissement town hall) in the presence of survivors and members of the families of those who disappeared.

In the meantime, both in Tehran and within Iran’s other major cities, thousands of calls for justice for the victims of the 1980s can be seen and heard. Their chorus is growing, and these cries have finally caught up with those with blood on their hands who thought they had succeeded in making Iranians forget their crimes.

Hamid Enayat is an independent analyst of Iranian politics based in Europe.