“The British are coming!”. Make that, “The British are here!”. London-based composer Dani Howard’s well-received 2018 Trombone Concerto is premiering at the Rose Theater, Jazz at Lincoln Center, on buzzing Columbus Circle, New York. It’s a spring-sunny Manhattan Sunday afternoon. Stroll up Central Park South. Wave the flag.

Peter Moore, principal trombonist of the London Symphony Orchestra, Professor of Trombone at the Royal Academy of Music, and dapper owner of the most terrifyingly electric blue suits in showbiz, was tooting his trombone. Turned out he had opted for a slightly quieter version of the suit. Don’t unsettle the natives.

Across Broadway Central Park was alive, the bustling Lincoln Jazz Center mall echoed with performers on each floor. The staggered escalator ride to the Rose Theater on the fifth floor was a journey through the Great American Performance Book – Jazz, Folk, Rap, Something Excellent, but Completely Unidentifiable. New York was strutting its Sunday best.

When Paul Revere alerted the militias of Lexington and Concord with his probably apocryphal warning in 1775 at the opening of the American Revolutionary War, the British army was stymied. In the Rose Theater, British revenge was sweet. On this May afternoon, Moore would see to it that his American audience was blown away.

No surprise there. He was, after all, heavily armed. A trombone at ten feet – memo to self, sit further back next time – in an enclosed space is an awesome weapon. In the acoustically taught arena of the Rose Theater, Howard’s powerful concerto and Moore’s virtuoso trombone took no prisoners.

Moore and Howard had come to New York (Howard, sadly, not in person) to tell how music can, in difficult times, carry a message of hope, bringing people together. Not in some schmaltzy, “there must be a better way” sermonising, but in ringing tones to stir the heart, for which the trombone is ideally suited.

I had listened to the Concerto several times online and thoroughly enjoyed it. But nothing can prepare the listener for the sheer power of a live performance. Usually concealed at the back of the orchestra, for obvious reasons of sound balance, in the lips of an accomplished soloist alongside the conductor, face on with an audience, the impact of the trombone was visceral.

Nowadays, for a fully immersive cinematic experience, vibrating MX4D seats rattle the audience. Forget the expense. Just call Moore.

Seldom featured in concerto form, the trombone has clearly been mistakenly overlooked. Howard is exploiting a gap in the market. The instrument has many voices, ranging from plangent questioning, through declamation, on to rasping derision. I’m sure I detected occasional subversive gales of rude, ironical laughter. No wonder the instrument needs its very own professor to keep it under control.

Howard’s concerto takes us on an engaging three-stage personal journey, Realisation, Rumination, Illumination. The intention is to invoke a mood in the listener rather than impose an agenda using more common programme music. Neither form is better than the other. Just different. And each member of the audience will respond to the music in his/her/its/their own way.

Simply, programme music is akin to observation from a distance. Howard’s music absorbs the listener completely. For instance, the likes of American composer Charles Ives in his Contemplation series sets a stage of third-party narrative, of town squares, marching bands and a dark Central Park with the listener installed as watcher.

On the other hand, in 1916, the underappreciated Danish composer, Carl Nielsen, wrote at the top of the score of his 4th Symphony: “Music is life, and like it, inextinguishable”. That is exactly the space I found myself in on Sunday afternoon.

As Howard’s music swept around the auditorium that trombone impacted each member of the audience uniquely. That’s her point.

The first segment, Realisation, is a wake-up call. And if you ever want to be woken up Moore and a trombone are far more effective than an Alexa alarm. “Peter, set your trombone for 7:00am”.

The music has a questioning, yearning quality, meant to be played “as if you are totally oblivious of your surroundings”. This trombone theme introduces someone engaged in everyday life, stumbling on their way in a baffling world, pretty much oblivious of their surroundings, the background chatter of the orchestra.

When the second Rumination segment begins the solo trombone conjures sympatico fellow trombone companions from the back of the orchestra, lightly reflecting the head honcho’s expressions. Engagement is under way. If the soloist had been David Cameron, he would have laid down his instrument at this point and told us, “We’re all in this together”. Or, in Downing Street boom-box argot, “Things can only get better”.

It seemed to me that the trombone’s utterances were gathering allies, building a narrative that even a single voice, which had first articulated in lonely isolation, actually mattered in a troubled world beyond its control. Don’t despair, there are allies all around you.

Then, on to segment three, Illumination. Not a trite solution to the world’s problems. That would be too easy, and this is not a preachy polemic. Rather a realisation that even that solo voice can matter in the world. The work ends as a celebration of the human spirit, acknowledging its resilience and capacity for facilitating positive change.

Howard’s score is scrupulously, and beautifully, crafted. Each voice in the orchestra is distinct. You find yourself listening to an intelligent musical conversation flitting across the hall. Harmonies and phrasing are sophisticated.

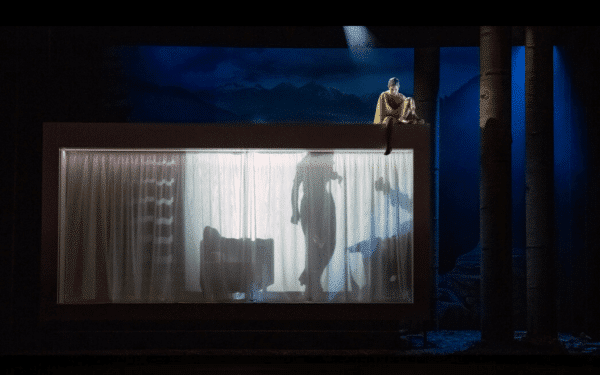

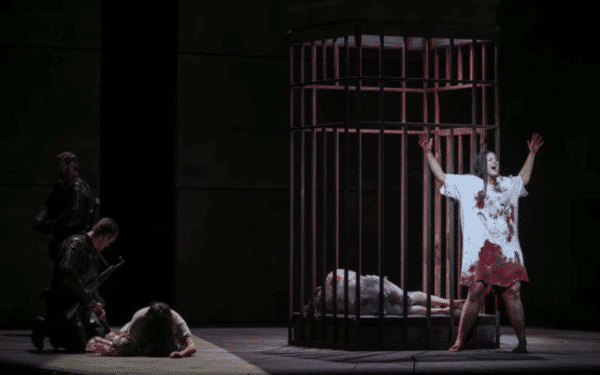

The musicality which pervades the work should not be equated with simplicity. Howard’s purpose is not so much to please the ear as to engage it. She achieves that while maintaining tonality. It is a great skill. I reflected on her chamber opera, The Yellow Wallpaper, in Copenhagen last August which similarly absorbed the audience.

Howard is no stranger to bringing wind instruments to the fore. Her series The Vino Encores which features Bassoon, Trumpet!, Oboe and Clarinet is must-see hilarious. Each featured instrument is accompanied by a glass of wine, the rim being carefully circumnavigated by Howard with a damp finger to imitate the eerie sounds of a hydrocrystalophone. The instrument was banned in Germany in the 19th century because it drove people mad! Who says ‘elf and safety’ freaks are new?

No risk with a wine glass. Carefully tuned to D, as the composer archly points out. Constant retuning – only to maintain perfect pitch, you understand – can result in severe inebriation. Howard is composing with tongue firmly in her glass. A serious composer with a sense of humour. Who would have thunk it?

Conductor, Chloe von Soeterstède was not sloshing the Chablis about in Manhattan, merely waving a stick. The French conductor is Principal Guest Conductor of the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, founded Arch Sinfonia, a chamber music ensemble based in London and champions works by contemporary composers.

She was in total command of The Orchestra Now, (TON) founded at Bard College, up the Hudson River in New York State in 2015 to gather young talent from around the globe. I was gobsmacked. The quality of playing, clarity of articulation and sheer damned firepower when required would credit any top rate household name orchestra.

TON’s roster of guest conductors is simply amazing. Leonard Slatkin, Neeme Järvi, Fabio Luisi …… the list goes on. The orchestra was in top form at The Rose working with Soeterstède, not only in delivering Howard’s work, but in the fiendishly difficult Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances that followed the interval.

When Moore’s trumpet unleashed its final salvo the Jazz Center audience, an awkward squad of difficult-to-please New York music aficionados, was ecstatic. On American shores, Dani Howard’s Trombone Concerto had conquered.

Write to us with your comments to be considered for publication at letters@reaction.life