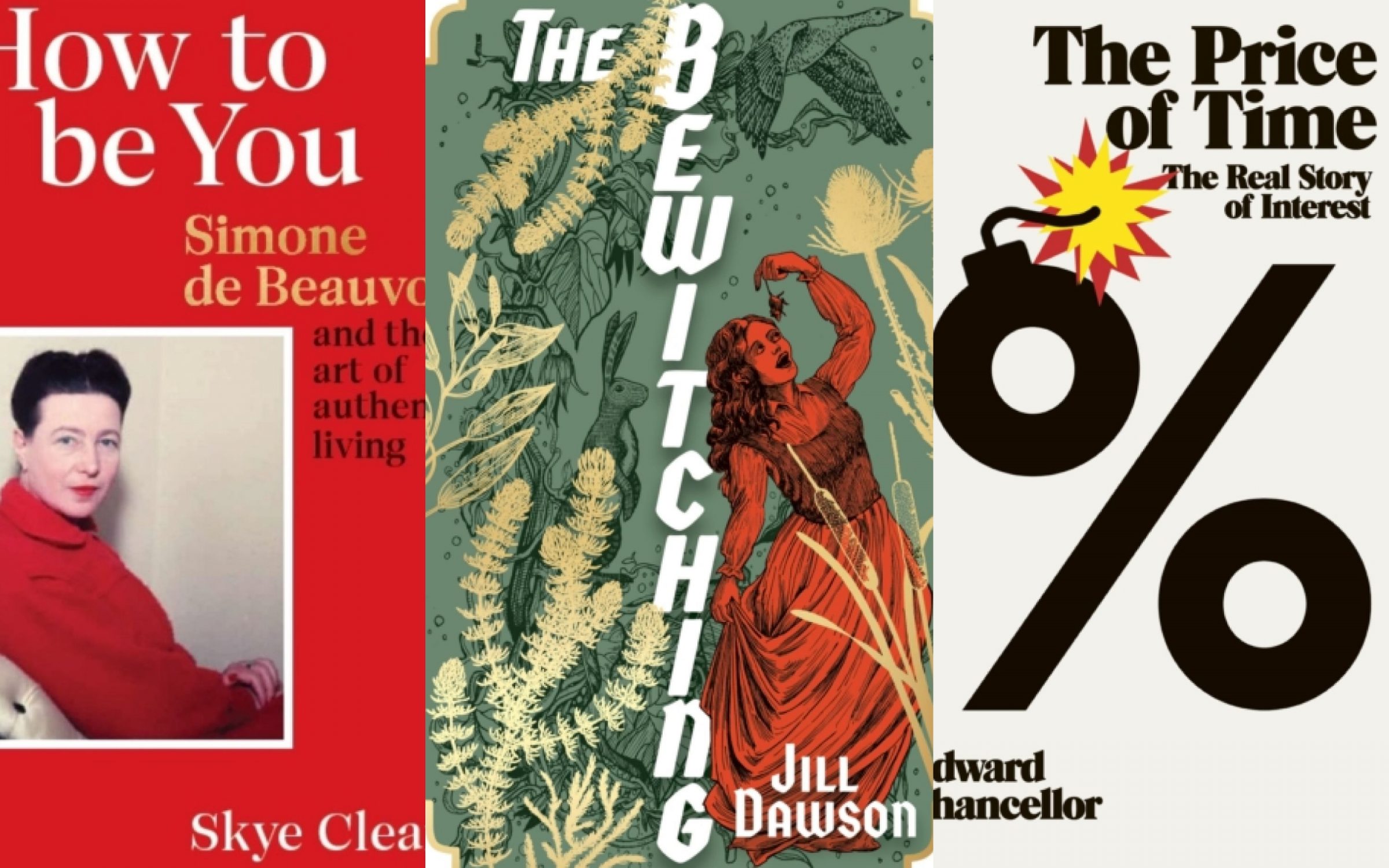

Welcome to our weekly Books Digest where we round up the new books you should and shouldn’t, be reading. This week How to Be You: Simone de Beauvoir and the art of authentic living by Skye Cleary, The Bewitching by Jill Dawson and The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest by Edward Chancellor.

For more books, take a look through our Books Digest Archive

How to Be You: Simone de Beauvoir and the art of authentic living by Skye Cleary (Ebury Publishing, £13.09)

Saffron Swire

The quest to be authentic in an age characterised by self-exposure is an arduous one. In all aspects of life – and especially in social situations – we are told to waltz into a room and just “be ourselves”, but what does this truly mean, and how do we go about invoking our truest selves?

When seeking clarity on how to be bona fide, the author and philosopher, Skye Cleary, says we should turn to the French existentialist philosopher, Simone de Beauvoir, who saw authenticity as a foundational element for the meaning of life. In her book How to Be You: Simone de Beauvoir and the art of authentic living, Cleary introduces the reader to the stepping stones of Beauvoir’s philosophy of existentialism and offers a guide as to how we can apply her ruminations to the modern-day trials and tribulations.

Cleary takes inspiration from the format of de Beauvoir’s epoch-making The Second Sex to address facts and myths about being a woman in three parts. Within the triptych, Cleary first discusses existential perspectives on what we can and can’t control and how femininity is configured. The second part explores the tension between ourselves and the world regarding marriage, parenthood and death. And the last focuses on choosing projects and how to evaluate which projects will support us in our creative endeavours and which are likely to lead us astray.

How to be You sits at the intersection of biography, philosophy and self-help. After reading it as a whole, the greatest strength of the book is Cleary’s dexterous ability to fuse philosophical analysis that applies to contemporary struggles along with her own personal – and commendably honest – insight. Moreover, Cleary does not shy away from addressing the pitfalls of de Beauvoir’s white-centric and middle-class feminism. But instead of merely fault-finding, Cleary addresses these gaps and offers a nuanced analysis of racism and intersectionality to reveal the power dynamics that continue to mould society.

So how can we conjure our “authentic” selves? Cleary posits that de Beauvoir would say to strive to be creative rebels and to free ourselves from oppression so that we can forge ourselves into responsible beings capable of transforming the world for the better. Thus to be “authentic” is to live in constant pursuit of self-creation. In writing How to Be You, Cleary has offered a short-circuit into doing just that.

The Bewitching by Jill Dawson (Hodder & Stoughton, £14.79)

Grazie Sophia Christie

In The Bewitching, accusations of witchcraft are an outlet for women spellbound by another force entirely: silence. They are silenced about their bodies, about the very basics of life and about what men have done to them. It is a silence under which they labour and muddle through, inarticulate, unprepared and vulnerable — until they learn to harm only each other.

Jill Dawson novelises the 16th century Warboys witch case from the perspective of both Alice Samuel, the accused, and Martha, the symbolically “deaf and dumb” servant to the Throckmorton girls, Alice’s accusers. Dawson treats witch trials not as an otherworldly, religion-fueled anachronism but as one stop on the spectrum of sexual violence. Alice’s story is intertwined with familiar narratives, where powerful men hurt women with impunity and go to great lengths to hide it. “The creature bearing all men’s scorn,” Dawson suggests, is not the witch, but the woman.

The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest by Edward Chancellor (Penguin Books, £16.69)

Maggie Pagano

Whether charging interest is a form of theft or essential to the smooth working of capitalism has been debated since time immemorial, or at least since the use of coinage by the ancient Babylonians in Mesopotamia in the 8th century BC.

Some historians date the use of interest even further, to the payment of blood money, to compensate for murder or other injuries. Others claim it was used to reciprocate gifts between prehistoric tribes. For many — like the French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon — interest is usury and parasitic and, if removed, would mean no more debt or bankruptcies and workers’ incomes would rise. In contrast, his sparring mate, Frederic Bastiat, a free-trader, argued that if interest were abolished, then only the wealthy would benefit.

Of course, charging interest is far more complex than the two Frenchmen would have had us believe. Yet the debate has taken on a new frisson after more than a decade of historically low-interest rates with some countries adopting negative rates. Indeed, financial historian Edward Chancellor, claims that low rates have undermined Western capitalism, leading to the lowest period of growth since the Industrial Revolution and that to him, it is not clear if capitalism can either thrive or survive within these conditions.

For Chancellor, interest is the price placed on the use of our time: we cannot value houses, shares or any other asset without this pricing mechanism. Without interest, we cannot take risks.

What’s more, Chancellor argues in his fascinating new book, The Price Of Time: The Real Story of Interest, that not only do low-interest rates create asset price inflation but they are also responsible for rising inequality, higher debt and the pensions crisis over the last decade.

As ever, Chancellor — who foresaw the 2008 Great Financial Crash — has stepped into the debate with impeccable timing, just as the central bankers are being forced to put up rates to contain soaring inflation which the bankers helped create by loading the markets with cheap money. Tant pis.