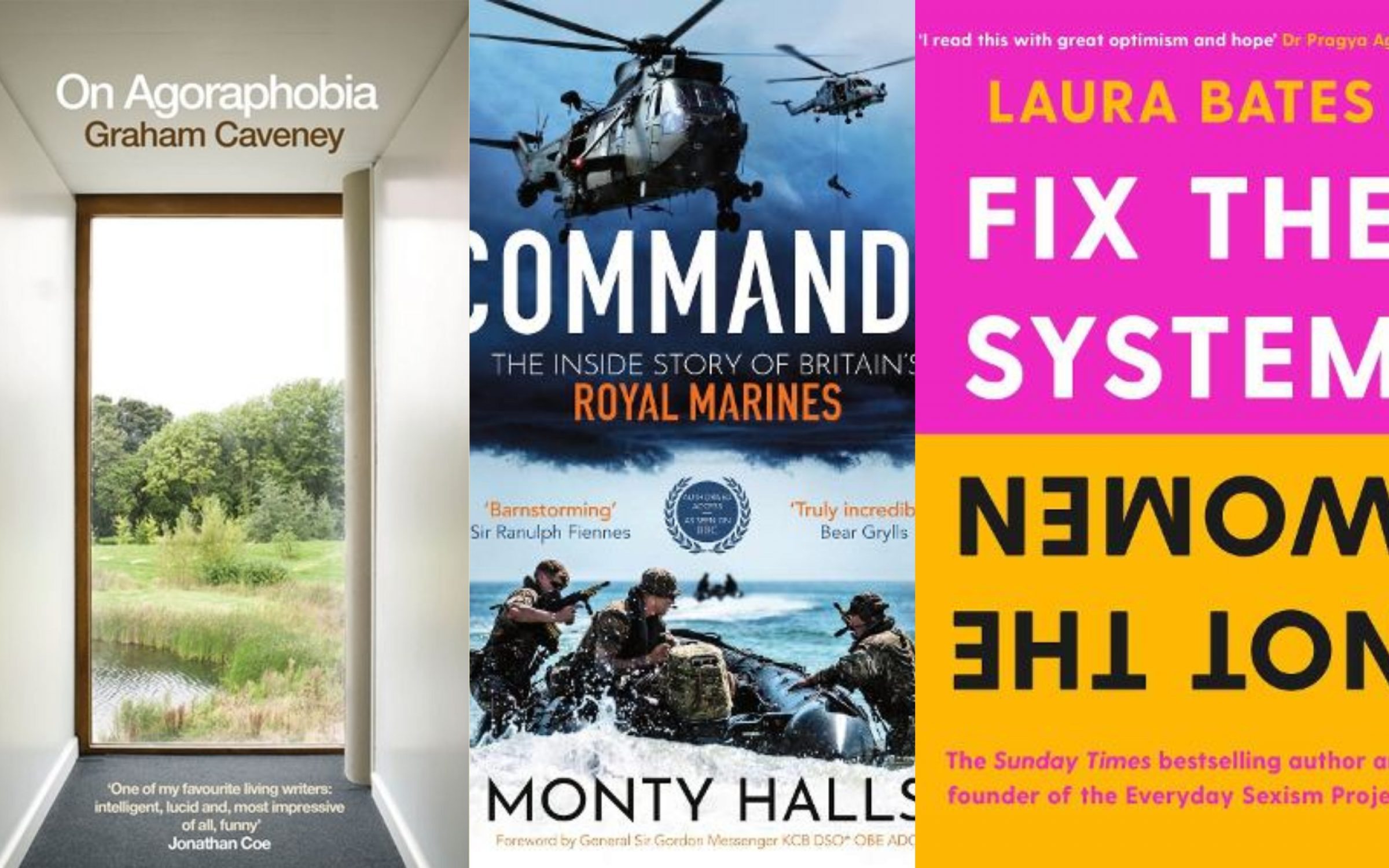

Welcome to our weekly Books Digest where we round-up the new books you should, and shouldn’t, be reading. This week features On Agoraphobia by Graham Caveney, Commando: The Inside Story of Britain’s Royal Marines by Monty Halls and Fix the System, Not the Women by Laura Bates

For more books take a look through our Books Digest Archive.

On Agoraphobia by Graham Caveney (Pan Macmillan, £11.45)

Alice Crossley

When Graham Caveney was in his early 20s, he began to suffer from what we now know as agoraphobia; “one day I realised I was too afraid to leave the house and I heard the word and realised it was being used about me,” he writes. He managed his condition by restricting his life to the small parameters of his Warwick university campus for as long as he could, but despite his best efforts, the disorder followed him into adult life.

Thirty years later, he still grapples with the anxiety disorder, losing himself in the pages of books and finding characters, and people, throughout history who have experienced agoraphobia, from Mrs Haversham to Boo Radley and maybe even Freud, he finds solace in their companionship.

On Agoraphobia is a unique book; Caveney’s writing is philosophical and self-aware, at times amusing (“I will tackle cyberspace once I’ve mastered actual space,” he writes of his evasion of social media) and at times painful (he was abused as a young boy).

The book is short and spacious, each page is broken up into small paragraphs leaving an unusual amount of white space. This is Caveney’s means of payback; “Agoraphobia,” he writes, “I want to write the word in the middle of the page, leave it stranded, surrounded with nothing but icy white space. My attempt at revenge.”

Commando: The Inside Story of Britain’s Royal Marines by Monty Halls (Ebury Publishing, £15.95)

Mark Fox

One of the great privileges of being an Honorary Officer in the Royal Navy is that I have been able to spend time with Royal Marines, individually, in groups and on a visit to their training centre at Lympstone. They form one of the five fighting arms of the Naval Service and are an integral part of the Royal Navy’s ability, and agility, to project itself at sea, under the sea, in the air and on land. This unique ability to provide fully integrated maritime, air and land activity is why the Royal Navy is the one indispensable armed service.

At the heart of this unique capability sit the commandos of the Royal Marines. There are many fighting forces around the world that are tough, capable, and better resourced, but none combine the rigour of training with the fostering of a corporate spirit, thoughtful determination, physical fitness, and mental resilience like the Marines. They are simply the best at what they do.

Commando: The Inside Story of Britain’s Royal Marines gives a fascinating and revealing insight into the community that makes up the frontline and support of this unique fighting unit. But there is a paradox here because one of the key characteristics of a Royal Marine is that they do not really like talking about what they do. I have never yet met a Royal Marine who is anything but modest and self-effacing. Indeed, it is often impossible to tell that you have met a Royal Marine unless you happen to know it or manage to coax it from them. And so, a book revealing the characteristics of the Corps seems to be something they would not like at all.

The Royal Marines are a well-established part of the Royal Navy having celebrated their 350th anniversary in 2014, but the Commandos, established by Winston Churchill during the course of the Second World War are a more recent phenomenon. Their training and their values have changed little in all that time. The Royal Marine commandos were then, as they are now, shining examples of what the best can look like, and make a significant contribution to making the Royal Navy Britain’s most capable fighting force.

Fix the System, Not the Women by Laura Bates (Simon & Schuster, £11.45)

Saffron Swire

Carry your house keys in a tight fist for self-defence, avoid dimly-lit areas at night, send your location so you are trackable, watch your drink like a hawk to stop getting spiked, cover up to avoid harassment, cross the street to avoid large groups of men, wear a wedding ring, fake a phone call…this is just a sample of the mantras women recite over and over so that they feel “safe” in public. And yet, despite this hyper-vigilance, one woman is still killed every three days in the UK. Why? Because we have wasted aeons of time telling women and girls how they can fix things, and how it is up to them to take the measures to feel safe when the reality is that women were never the problem.

Herein lies the nub of Laura Bates’ timely book Fix the System, Not the Women. In the book, Bates exposes the systemic prejudice rotting at the core of our five key institutions — education, politics, media, policing and criminal justice. Bates has spent a sizeable part of her life archiving sexism after founding the Everyday Sexism Project a decade ago which has now received over 200,000 stories of sexism and misogyny detected everywhere from the playground to the boardroom.

In Fix the System, Not the Women, Bates weaves these uncomfortable first-hand accounts with staggering statistics to expose the interlocking systems of oppression that define reality for millions of women. For example, did you know that one in four women in the UK will experience domestic abuse? Or that 85,000 women a year are victims of rape or attempted rape? That 600 sexual misconduct allegations were made against Met police officers between 2012 and 2018, with only 119 upheld?

The system — whether it is a gaggle of horsehair-wigged lawyers letting perpetrators off the hook, Met police officers exchanging sexist messages, or journalists who sexualise female MP’s because they (shock horror) have a pair of legs — is failing women. While Fix the System, Not the Women can make for a disheartening reading, it is a lightning-bolt of a wake-up call for these institutions to embrace root-and-branch reform if misogyny is to be tackled at a systemic level. “It’s not the skirt,” asserts Bates, “it’s the system.”