Margaret Keenan, who turns 91 next week, became the first person in the world to receive the Pfizer Covid-19 vaccine injection as part of the UK’s mass vaccination programme at 6:31 this morning. Known as Maggie, the grandmother of four who only retired four years ago, was the first Briton to receive the jab at the University Hospital Coventry & Warwickshire, thus kicking off the biggest vaccination programme ever launched by the NHS.

The UK is the first country in the Western world to start the Covid-19 vaccination roll-out after British regulators approved the new Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine last week. The government’s plan is to administer 800,000 doses over the next few weeks to people in the priority groups, and four million doses by the end of the month. The vaccines take 28 days to take full effect and require two shots – a first dose and a booster 21 days later to confer immunity. In total, the government has secured 40 million doses of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine, enough to cover 20 million people.

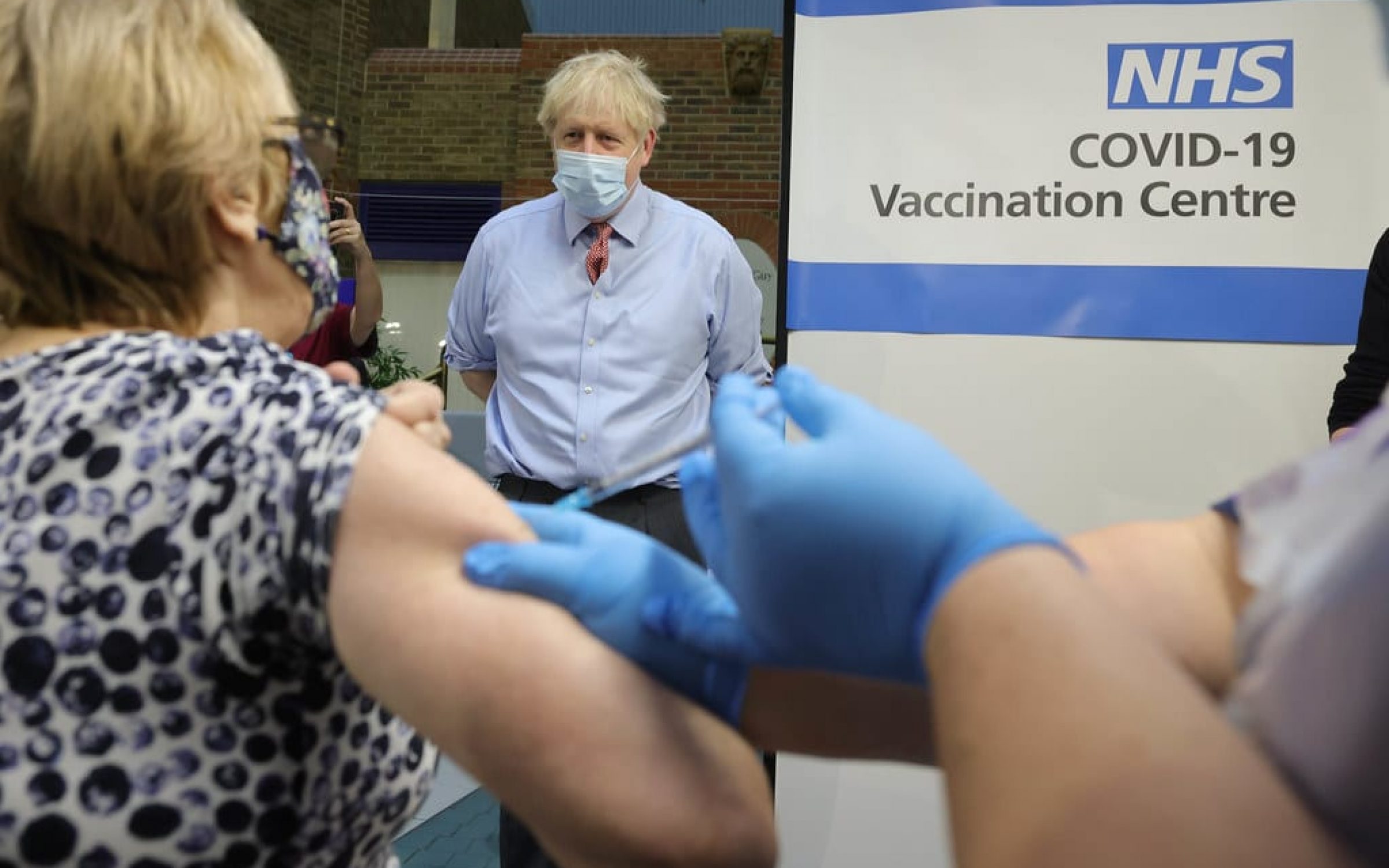

The NHS has designated 70 hospitals around the country as vaccination hubs. Care homes, GPs surgeries, as well as sports stadiums and conference centres will also be put into use once the logistical challenges have been resolved. To help with the mass roll out, the government is recruiting 30,000 volunteers who will be trained to administer the vaccine.

The vaccines will be distributed for free on the NHS – meaning no one will be able to jump the queue by paying. Government guidelines are prioritise vaccinating those most at risk from the disease first. Elderly care home residents and their carers are at the very front of the queue. The over-80s and frontline workers in the NHS and social care come next. After that the government will be prioritising the over-50s – moving from the most to least elderly – plus the extremely clinically vulnerable and those with underlying health conditions.

The government has stated that it expects the majority of people on its vulnerable list to have been vaccinated by February.

Meanwhile, the rest of the population aged between 16 and 50 will probably not receive a vaccine until well into 2021, when the second phase of vaccinations begins. Most children will not be vaccinated as they are not deemed vulnerable to the disease. Pregnant women are also advised not to be vaccinated until they have given birth as the vaccine had not been tested on them.

Indeed, we are still in for the long haul. The sheer logistical challenge of ensuring a smooth supply of vaccines and storying them at an ultra-low temperature should not be underestimated.

Already, manufacturing difficulties has slowed the distribution of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine. The UK government had hoped to receive 10 million doses by the end of the year, now it looks like the number will be less than half. Furthermore, 20 million immunisations doesn’t even completely cover the roughly 25 million people on the government’s priority list.

The Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccines which the government hopes might make up some of the shortfall has also faced issues. While the Health Secretary Matt Hancock expressed hopes that the vaccine would be approved in the “next couple of weeks” there has been some confusion over the results of its trials. This vaccine has also been hit by manufacturing delays which mean the UK government expects to only receive four million doses by the end of the year, as opposed to the hoped for 30 million.

Moderna is also seeking approval for its vaccine from the UK’s regulators. Moderna’s vaccine appears to be highly effective and easier to store than Pfizer’s. However, the UK government has only secured five million doses of this particular vaccine.

Appearing on Good Morning Britain, Hancock actually wept with relief even as he warned “we can’t blow it now”. Later this morning on BBC Breakfast, Hancock, while admitting we still had “months to go”, said life could return to normal “by the spring, I hope, certainly by the summer”.

Also appearing on the programme was Professor Stephen Powis, national medical director of NHS England, who backed up Hancock’s hope. The Professor said the vaccination programme felt “like the beginning of the end”.