If the past is a foreign country where they do things differently, Look and Learn was another world. They came bundled by the dozen, tied with white cotton twine, and my main dealers were old ladies manning jumble sale stalls. For little more than a few coins and a winning smile, they supplied my drug of choice for years. Behind me the main table, piled high with clothes, heaves like a chicken being simultaneously plucked by dozens of adults; in front, I see wonderful things – each hidden in a copy of Look and Learn.

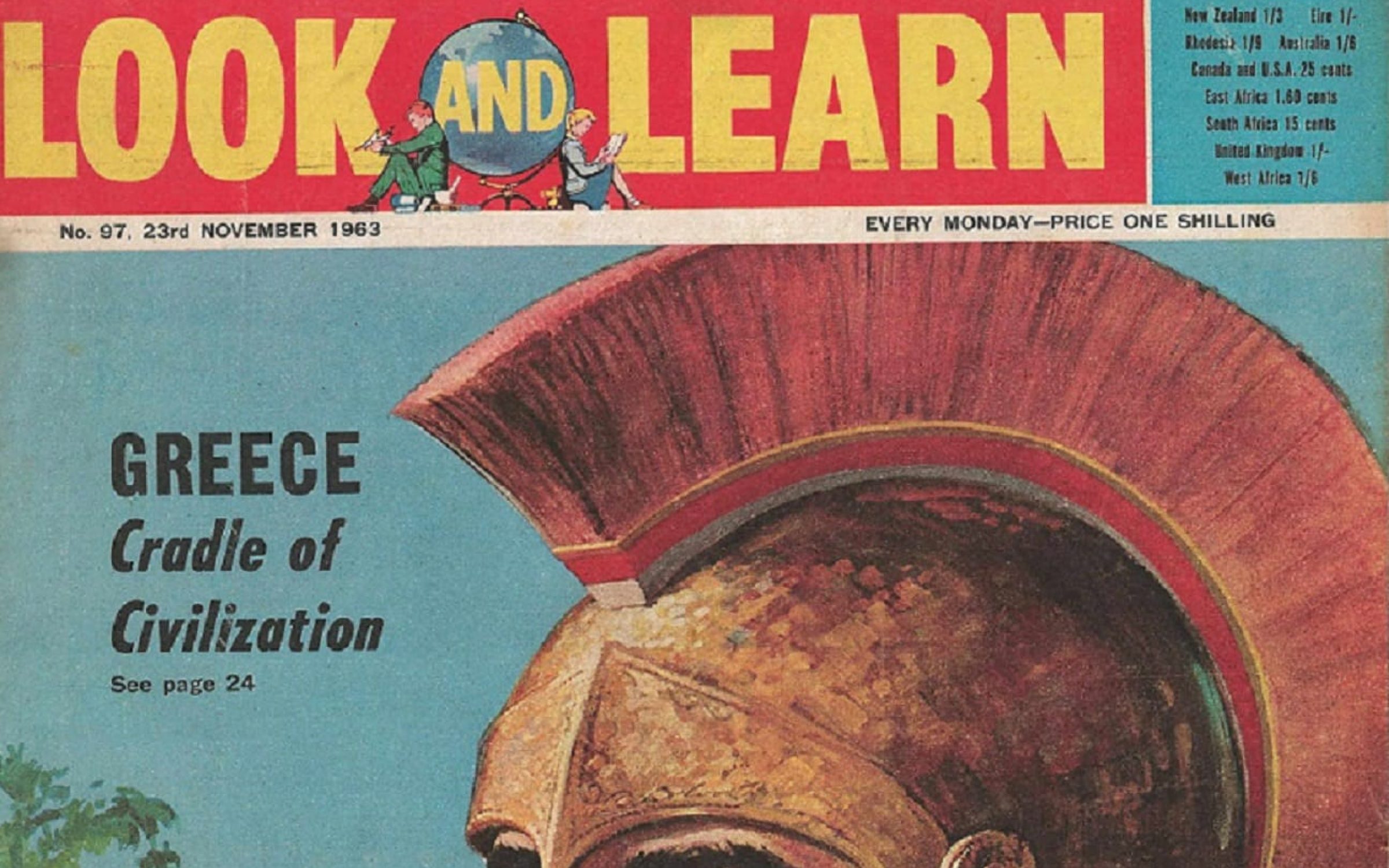

Even then, I dimly sensed adult approval. A relatively expensive publication at its 1962 launch – one shilling, rising to 40p in 1981 – Look and Learn was what the magazine industry called a ‘parental buy’. For some reason, only my older sister was allowed to get a magazine delivered fresh from the newsagent: something called ‘Jackie’ (mysteriously female; jealously hidden). But I was more than happy with these huge-format, vividly illustrated, and enthrallingly wide-ranging decade-old copies. And while I possess a very good degree from a well-known university, I still think that most of what I know comes from Look and Learn – and it certainly kindled a life-long love for the places where reading can take you…

The range and depth of stories was extraordinary, and would no doubt surprise most modern children. This “treasure house of exciting articles, stories and pictures”, as its first editor called it, was like one of Cavafy’s Phoenician trading stations. The first issue had Prince Charles, as well as his namesake Charles II learning of his father’s death by Roundhead in France – and later escaping from the New Model Army after the battle of Worcester:

“Breathlessly he flung himself into a narrow, dark alley and hid in a shadowed doorway. The raucous shouts and stumbling footsteps of the Roundhead soldiers chasing him went past the entrance to the alley and faded away in the distance. Panting, he huddled himself against the crude wooden doorway and rested his unshaven face against the splintered oak. For the moment he was safe.”

There were features on van Gogh and Roman history, natural wonders and the Grand Canyon, Parliament’s story (the centre page spread!), Japanese children celebrating Shichi-Go-San, Sinbad and Sir Richard Burton, Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog) and how to keep Bassett hounds, and much, much more. It simply blew all previous educational magazines out of the water and, as pulp historian Steve Holland recalls in his 111 page monograph, which lovingly tells its history: “British readers—old and young—had never seen anything like this before.”

Holland quotes the first editor David Stone, who promised that “Look and Learn is not a comic, or a dusty old encyclopaedia pretending to be an entertaining weekly paper. It is really like one of those fabulous caravans that used to set off to strange and unknown places and return laden with all sorts of wonderful things. In our pages is all the excitement, the wonder, the tragedy and the heroism of the magnificent age we live in, and of the ages which make up the traditions which shape all our lives.”

That caravan eventually extended to over 1,000 issues. For at least two generations of British children (and others overseas – one hapless editor, chaperoning six children who had won a competition to join John Blashford-Snell in Kenya, found a dusty copy in a remote village shop), it was as exciting as the kind of gypsy caravan party you get in Peaky Blinders.

Nor was it chauvinist: Look and Learn roamed worlds past, present and future. In 1963, in an article on “The World’s Thinkers”, it was asking questions like “Are men and women equal?” An evergreen combination of expertise and enthusiasm proved as endearing to young readers as old. The magazine had also arrived on the shelves larded in praise, albeit from the somewhat improbable likes of Lord Boothby, Hugh Gaitskell, Eamonn Andrews and, more plausibly, speed-merchant Donald Campbell. Within a few issues it was selling a million copies weekly, before settling down to a still respectable 300,000 – well over twice The Guardian’s current daily figure.

Most boys may preferred such fare as The Beano, of course, while girls preferred to devour their Boyfriend, but Look and Learn readers got Leonard Cottrell’s Golden Age of Greece, Patrick Moore on space, inventors and inventions, historic castles, Crusaders, pirates, the Peasants Revolt, and even “John and Jane Citizen” on governments, laws, and their impact.

For years it made good money, and while there were relatively few advertisers, their roll-call remains deeply evocative for children of all ages: Airfix and Scalextric, Hornby and Platignum pens. There were also successful books and annuals, alongside a variety of spin-offs and several more or less short-lived side projects.

Although the unions could be tedious – one editor told Margaret Thatcher that “wonderful magazines like Look and Learn were being strangled because of the unions”, the team producing it had fun. Picture editor Lyn Marshal’s Sunday lunch went on all day: “Five courses, starting with champagne in the garden.”

Look and Learn petered out in the 1980s, but left behind a legacy that still stirs the soul. Aficionados today particularly rate the run of outstanding artwork by some truly great illustrators (originals can still be picked up remarkably cheaply, and the magazines on Ebay are great value, too).

Holland has a great story about the legacy of this wonderful magazine, told by its last editor, Jack Parker: “I got into a taxi once and the driver said ‘I can’t help noticing that you have Look and Learn on your nametag. Are you involved?’ I said ‘Yes, I’m the editor.’ ‘I would like to thank you very much and shake you by the hand,’ he said, ‘because my son was an absolute no-no; he didn’t want to read, he didn’t want to do anything when he was younger and we decided we had to do something and so we took Look and Learn. And he was hooked on it and his whole attitude changed: he used to love reading and looking at the pictures and eventually he went to university and got a degree. And I thought, ‘Well, in my career if I never do anything more than that, then I’ve actually achieved something.’”

Me, too: without Look and Learn, you almost certainly wouldn’t be reading this.