“The doctor can’t see you now”. “Jayzus, Dr. Walsh knew I was coming into the County Hospital for me bunion operation. Who’s going to put me to sleep now?”

It’s probably a slander to even dare suggest that Dr Thomas Walsh, an anaesthetist at Wexford County Hospital in 1951, ever neglected any of his patients in pursuit of his passion, opera. But in November 1951 Dr Tom – as he was affectionately known in Ireland’s southern county town – was likely to be hot bedding between his place of work and Wexford’s Theatre Royal.

There, he was overseeing the production of The Rose of Castile by Irish composer, Michael William Balfe. This was the work from which Wexford Festival Opera sprang, beefing up to two productions every year in 1955, then mostly three from 1963 onwards.

Dr Tom was leveraging the local musicianship in church choirs and instrumental ensembles and his ability to charm a star cast of principals from the trees. Maureen Springer (soprano) and Murray Dickie (a Scottish tenor) who sang the roles of Elvira and Manuel in 1951 were already embarked on international careers – Glyndebourne, Covent Garden and Vienna State Opera.

Quite a catch. How the hell did Walsh do it? The Wexford effect must have been electric. Dickie and Springer married. The Radio Éireann Light Orchestra was hustled down from Dublin. Wexford Festival Opera was born.

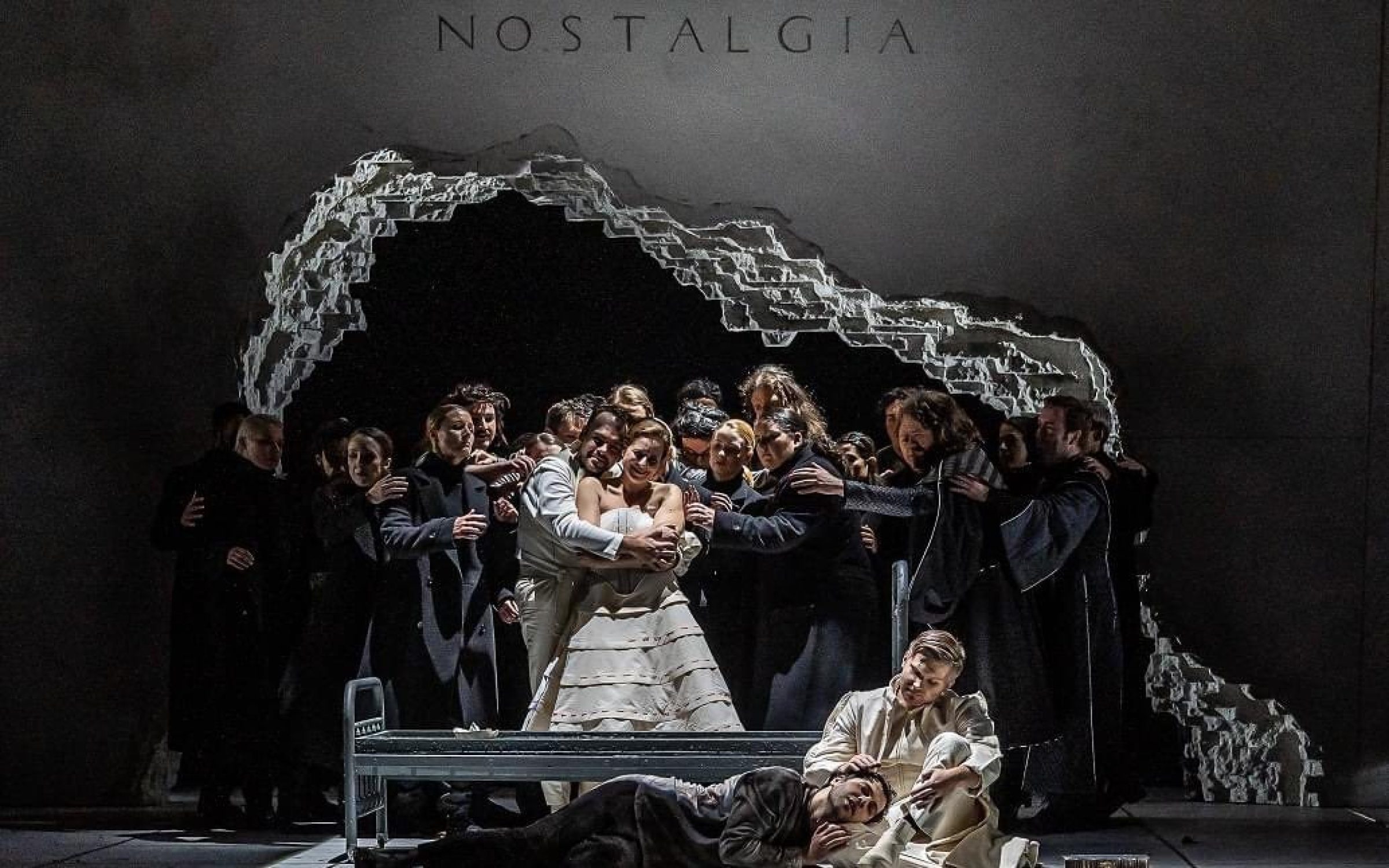

Shut Your Eyes and See – a typical James Joyce oxymoron – was the slogan for this year’s festival. The theme was Magic and Music. Up to a point. Main stage operas, Dvorák’s Armida and Halévy’s La Tempesta, are both closely associated with sorcery. The third had scant connection.

I loved, but strained to find much “magic” in David’s Lalla-Roukh, apart from Director, Orpha Phelan’s inspirational wheeze of having the story conjured out of an old book by a tramp. There was also a feeling that La Tempesta had fallen out of last year’s old Shakespeare theme cupboard. But, what the hell? It’s Wexford, and I’m at risk of dancing on the head of a critical pin.

The festival focus has always been on mainstage productions, but over the years Wexford has seen a burgeoning of smaller operas, concerts and events. Wexford Factory, a programme inaugurated by Cucchi in the dark covid days of 2020 to encourage performing and production talent, is already proving a deep well of skills from which these previously peripheral events now draw.

This was a bumper year. I filled my days with Cinderella, by wunderkind pianist and composer Alma Deutscher; The Master, a story about the inner life of the author Henry James, by Alberto Caruso; and The Spectre Knight, a comedic tale of enchanted courts and courtship, by Alfred Cellier.

Deutscher wrote Cinderella as an opera at the age of 10, when most of us were still struggling with illustrated versions of the book. This was no kid’s fancy. It was rewritten in a dream world of the heroine, full of luscious narrative music and full of comic quips, occasionally involving interrogating the maestro about the goings on on-stage.

The Spectre Knight involved Viola, the daughter of a banished duke, who lives in a magic glen. The glen is haunted by a Spectre Knight, who turns out to be Otho a distant cousin. Viola falls in love with him. All is revealed. The banished duke is restored and all is well.

As an hour of fast-paced hokum with crazy props in the confined space of the Arts Centre, this took some beating. It was impossible not to be involved. On exit after curtain call Second Lady, Erin Fflur, reached down, picked up my reading glasses which had slipped from my pocket onto the floor and handed them up to me. Audience engagement.

The star turn of the “fringe” was The Master. The libretto by Irish author, Colm Tóibín was frighteningly powerful as he took us through the troubled and ambiguous life of American author, Henry James. Characters who had moulded his life – notably Constance Fenimore Woolson, who assumes the role of muse – appear to James, walking him through his life and art and encouraging him to live in the real world, not just through his work.

This was a ghost story par excellence and emotionally draining. In future years Cucchi would be well advised to consider bringing works such as this, which rest on indigenous Irish talent, onto the main programme. Relying only on 19th century works, as she did this year, is missing a trick.

Also on offer was Les Selenites, a commissioned opera, music and lyrics by Irish composer Conor Mitchell, dealing with the interaction of four performing artists involved in the birth of cinema, dream-play and fantasy.

The beautifully produced programme is worth a shout-out. It runs to 221 pages. Editor and Graphic Designer, Roberto Recchia and Features Editor, John Allison have excelled themselves. The basics, lists of artists, synopses, etc. are all professionally done. Goes without saying.

It is the depth of the background research and accompanying essays that make this more than a programme, an essential “must read” in its own right. Now, it is supplemented by a comprehensive YouTube Channel which provides background insights and up to date news on what the Wexford crew is up to through the year.

The town also buzzes with a concurrent art festival, a slew of concerts and pop-up events. Truth is, three days is no longer enough to fully explore everything on offer. And yet, the festival retains its feeling of intimacy.

The Friends Lounge in the theatre still provides free coffee and craic. Executive Director, Randall Shannon and Cucchi still ornament the door greeting operagoers. The Lobster Pot restaurant at Ballyfane, under new ownership, is as welcoming and mouth-watering as ever. The Galley cruising river restaurant on the River Barrow at New Ross seems still firmly settled in the Barrow silt, having sunk four years ago. Anyone up for a crowdfunding campaign to refloat her?

This year the annual Dr Tom Walsh lecture was delivered by Patrick Spottiswoode, founder of Globe Education, who returned to last year’s festival theme, Shakespeare, explaining that the rough, down to earth language of England championed by the great playwright engaged so many opera composers and librettists in the 18th and 19th centuries.

I’m sorry I couldn’t make the lecture. If I had, I’d have asked him what on “earth” he was talking about, as all the librettos of mainstream Shakespeare-based operas I’m aware of were written in Italian. Shall maybe turn up to heckle next year. I think Shakespeare’s stories were simply irresistible. I’m sure Dr Tom would have bustled down from the County Hospital to hear what Spottiswoode had to say, amazed that his zany enterprise of 1951 has endured, flourished and morphed into one of the “must go to” events in the international opera calendar today.