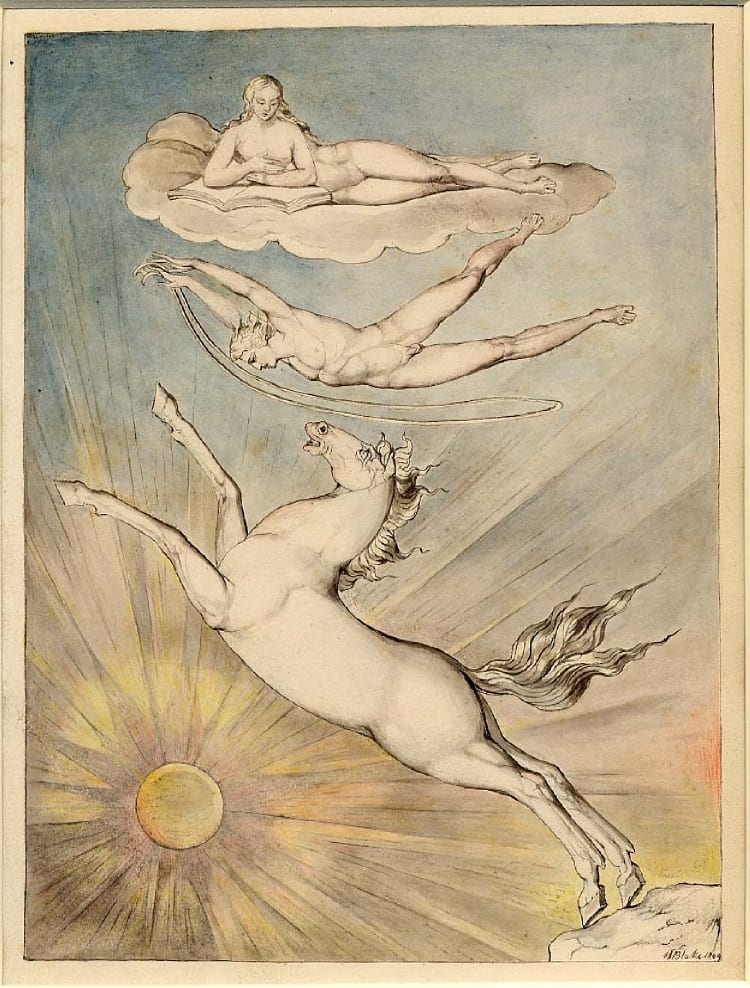

Fiery Pegasus, William Blake, 1809, The British Museum

For these days of national (not to say international) crisis, I have chosen an image that seems to me to carry a healthy national message. It’s a celebration of Shakespeare by one of our most eccentric and inspiring artists, William Blake (1757-1827). Blake is known for his poetry as much as for his very personal approach to painting. He invented his own techniques, and published his work, literary and visual, in books he designed and printed himself. (He was no stranger to self-isolation, but he had a loyal wife as company and studio-assistant.) He also made illustrations for other books, the Bible and Shakespeare among them. You may have seen the large display of his work at Tate Britain this winter.

This wonderful drawing in pen and watercolour, measuring 231x 173 mm., is one of a small set of designs, all in the British Museum, for As You Like It, Henry VIII, Julius Caesar and Hamlet, as well as this, for Henry IV part I.

The at first puzzling subject illustrates an image from Sir Richard Vernon’s lines in Act IV scene 1: “I saw young Harry, with his beaver on,/ His cuisses on his thighs, gallantly arm’d, Rise from the ground like feather’d Mercury, /And vaulted with such ease into his seat,/ As if an angel dropp’d down from the clouds,/ To turn and wind a fiery Pegasus/ And witch the world with noble horsemanship.”

Uncertain what it might mean, critics have thought the subject celebrated Shakespeare himself: his Genius dropping from a blue heaven inhabited by a literary nymph with a large book – Shakespeare’s works perhaps? – to lasso a magnificent rearing horse, as if to guide it over the blazing sun that rises from below. There is a suggestion of the horses of Apollo, god of light and of poetry, and the implication that, rather than the heroic young Prince of Wales, Shakespeare himself, with the “noble horsemanship” of his verse, can “witch” us all into a better state of being, just as King Henry V would bring England, as Shakespeare wants us to think, to a new state of greatness in his reign.

I admire the brilliant openness of the design of this sheet, the unexpected relationship of the figures, the horse arching between them with an inexpressible sense of joy – and that full-orbed sun blazing across it all. All the Shakespeare subjects in this set of Blake’s, with the exception of one showing Jacques and the wounded stag from As You Like It, are of scenes in which the material world interacts with the ghostly or spiritual, so I think we are entitled to see this evocative image as a vision of how the real world is uplifted and transformed by the power of the poetic and artistic imagination.

Blake, Shakespeare – two geniuses who might be sufficient to keep our spirits up in these dark days.