Word Watch: Vibrancy

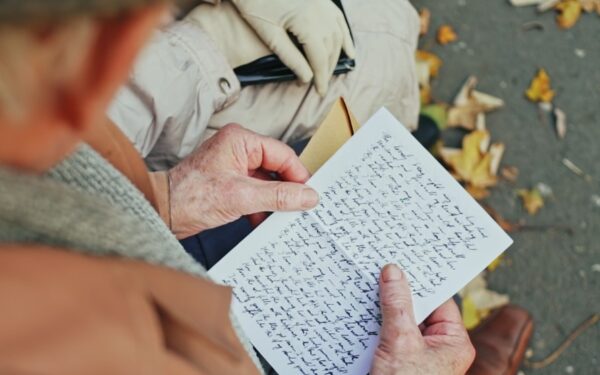

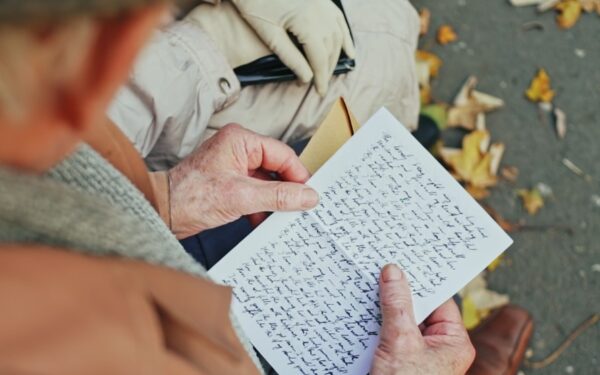

Is it really a compliment for one’s home to be described as “vibrant”?

Already a subscriber? Login to your account

Already a subscriber? Login to your account

Subscribe to Reaction for just £8/month and receive unlimited access to the site, our daily email with analysis every evening and invites to online events.

Includes Iain Martin’s weekly newsletter on politics, daily columnists including Tim Marshall, Maggie Pagano and Adam Boulton. Unlimited access to all the stories by our brilliant team of journalists, our daily email with analysis every evening and Reaction Weekend featuring coverage of life, culture and sport. Plus invites to our events. Your support also helps us offer training to the journalists of the future through our Young Journalists Programme.

Is it really a compliment for one’s home to be described as “vibrant”?

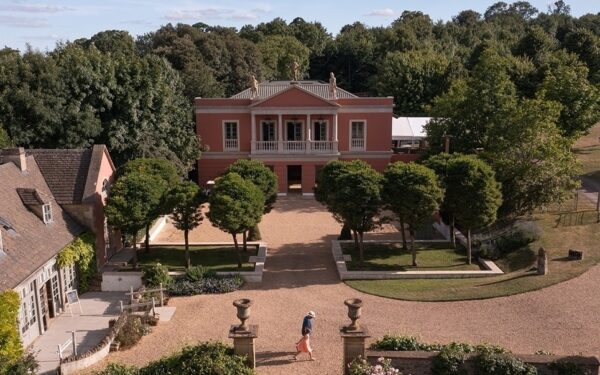

Ring heads and Ring virgins alike descended on the Cotswolds for an evening of Wagner at Longborough Festival Opera.

Spectators arguably owe the grand scale of today’s opening ceremonies to cold war rivalry.

Subscribe to Reaction and receive unlimited access to the site, our daily email with analysis every evening and invites to online events.

© Copyright 2024 Reaction Digital Media Limited – All Rights Reserved. Registered Company in England & Wales – Company Number: 10166531.