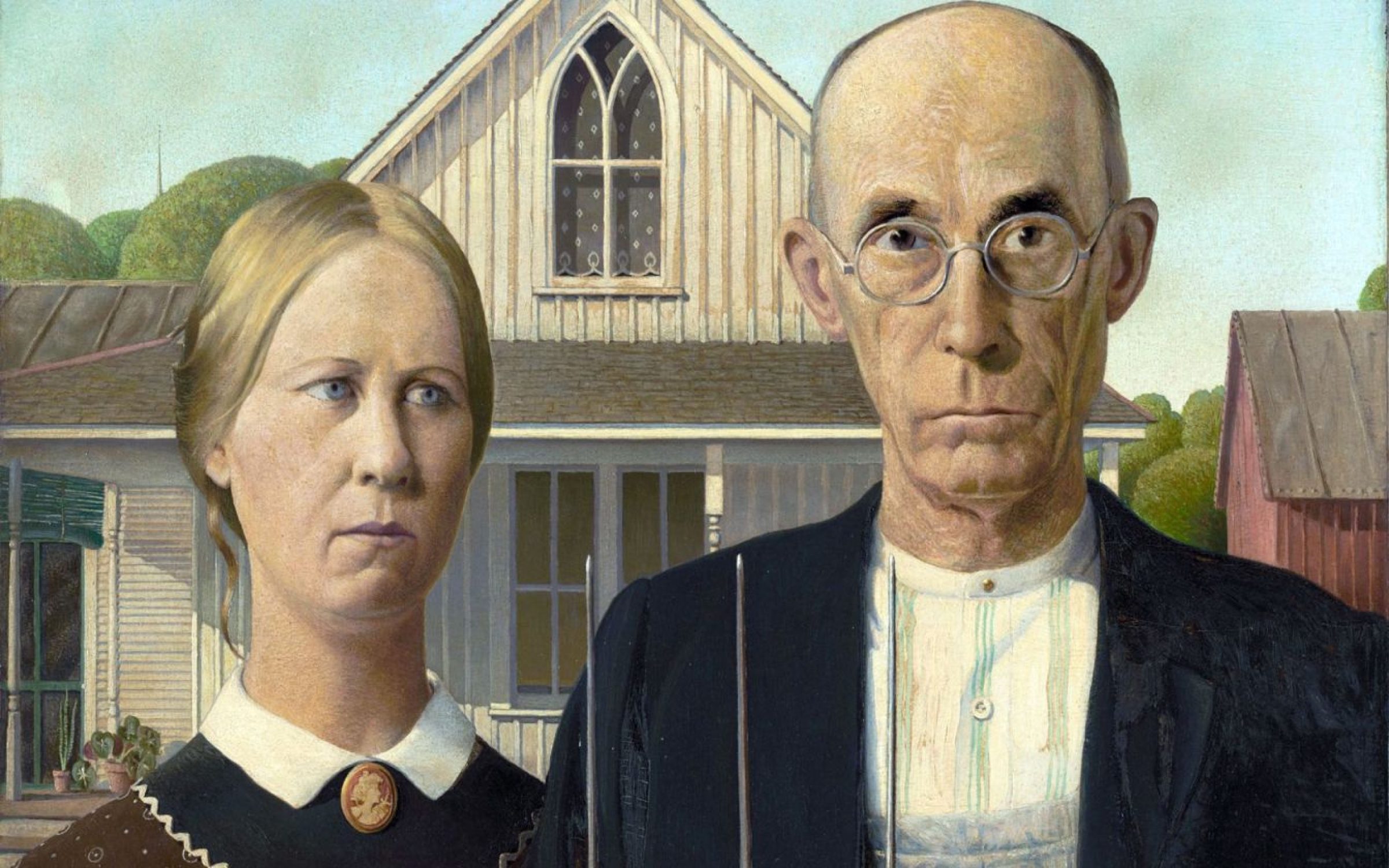

This is one of the best-known of all American paintings. At first sight, it seems an archetypal image of the god-fearing, unpretentious character of the people who emerged from the hard-working life of rural America in the early 20th century, the lifestyle recorded by John Steinbeck or Sinclair Lewis in novels of the 1920s or 30s. But that analysis breaks down as we look more closely at the details of the picture.

As we become better acquainted with these two people, we are increasingly convinced that they are not what they seem. Are they playing a game with us? Isn’t the three-pronged fork, held aggressively as though it were a trident, slightly absurd? Those long faces, the somewhat forbidding seriousness with which they confront us — can the pair hold those poses and expressions much longer? Would they break into giggles if we turned our backs?

We learn that the “couple” in “American Gothic” were not a couple in real life: the man was Grant Wood’s dentist, the woman the artist’s sister. The little house was a building that intrigued Wood as he happened to pass it, and apart from its quaintness struck him as slightly ridiculous with its incongruous gothic window — after all, the house wasn’t a chapel. It can still be visited, the Dibble House in the small town of Eldon, Iowa. The whole thing is a fabrication, assembled from carefully selected but quite disparate details to make up a composition that is really just that: a fiction, a fantasy.

American Gothic 1930

Oil on board 30 ¾ x 25 ¾ in. (78 x 65.3 cm.)

Art Institute of Chicago via wiki commons

People have enlarged that sense of fantasy by suggesting that the subject is an allegory — a rather grand way to interpret such a “down home” image. But the “trident”-fork surely does suggest the attribute of some avenging Greek god. And maybe that charming cameo pinned to the woman’s collar has overtones in Greek mythology.

It was clever of Grant Wood to imply a link between the geometrical patterns of the man’s shirt and overalls and the detail of the house front; between the woman’s plain patterned black dress or apron and the net curtain in the gothic window. The whole picture has a unity that depends on these small correspondences.

It also depends on the ambivalence of our response to it, which reflects our perception of the characters it portrays. Are we laughing at their humourless solemnity, or are we secretly admiring their simple decency and dependability? Of course, we don’t know anything about their decency and dependability: all we know is what the artist has given us. There they are: close up, unflinching, and despite their ambiguity, not difficult to get to know. And just as when watching a play we take the values of the characters as they appear on the stage, so here we enter into the world that Wood has evoked so vividly for us, and identify and sympathise with the couple as he presents them.

The picture was painted just as the Wall Street Crash was wreaking havoc with American confidence and the world economy. Is it a reminder that scattered across the spaces of that vast country unknown people were getting doggedly on with lives remote from high finance, perhaps indifferent to such arcane matters, yet worryingly caught up in them willy-nilly? Maybe that’s the real reason for this couple’s stern demeanour.

The enduring popularity of “American Gothic” is testimony to its ability to speak very directly to Americans, and by extension to all of us.

Andrew Wilton was the first Curator of the Clore Gallery for the Turner Collection at Tate Britain and is the author of many works on the artist.