Seventy years ago county cricketers, many doubtless happy to have put their winter jobs behind them, were back in the nets, preparing for the new season that for most would begin in the last week of April. It promised to be an interesting summer, also an important one, for there was an Australian tour to come in the winter. With this in mind, there had been no MCC tour in the winter just finished; better to give players like Hutton, Washbrook, Edrich, Compton, Evans and Bedser a winter’s rest.

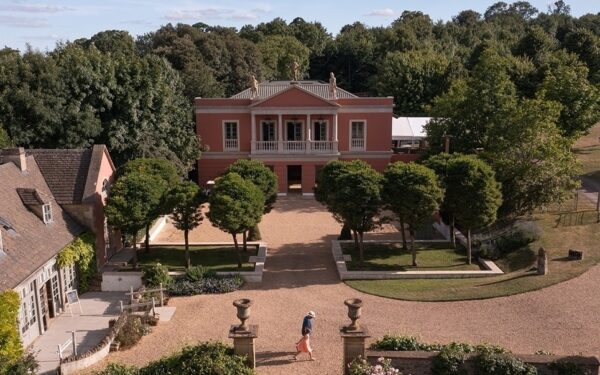

All eyes on Paris ahead of Olympics opening ceremony

France’s opening ceremony promises to be quite the spectacle, provided security threats can be kept at bay.