As part of Labour’s proposed men’s health strategy, the shadow health secretary Wes Streeting is looking to address an alleged “crisis in masculinity” that is costing lives. According to Streeting’s predictable diagnosis, men are killing themselves at a disproportionate rate precisely because they are not talking enough. The crisis is to be managed by expanding mental health services for schoolchildren, alongside encouraging boys and men to be “more open”.

There is an issue here: our culture is uniquely open about mental health already. Never have we spoken so much about good or bad mental health (let alone diagnosed mental health disorders, and prescribed anti-psychotic drugs), yet this has had little effect on male suicide rates. Even with the profusion of “open-up” campaigns to get men talking more about their feelings, men continue to account for three-quarters of suicide deaths, a trend that has remained consistent since the 1990s.

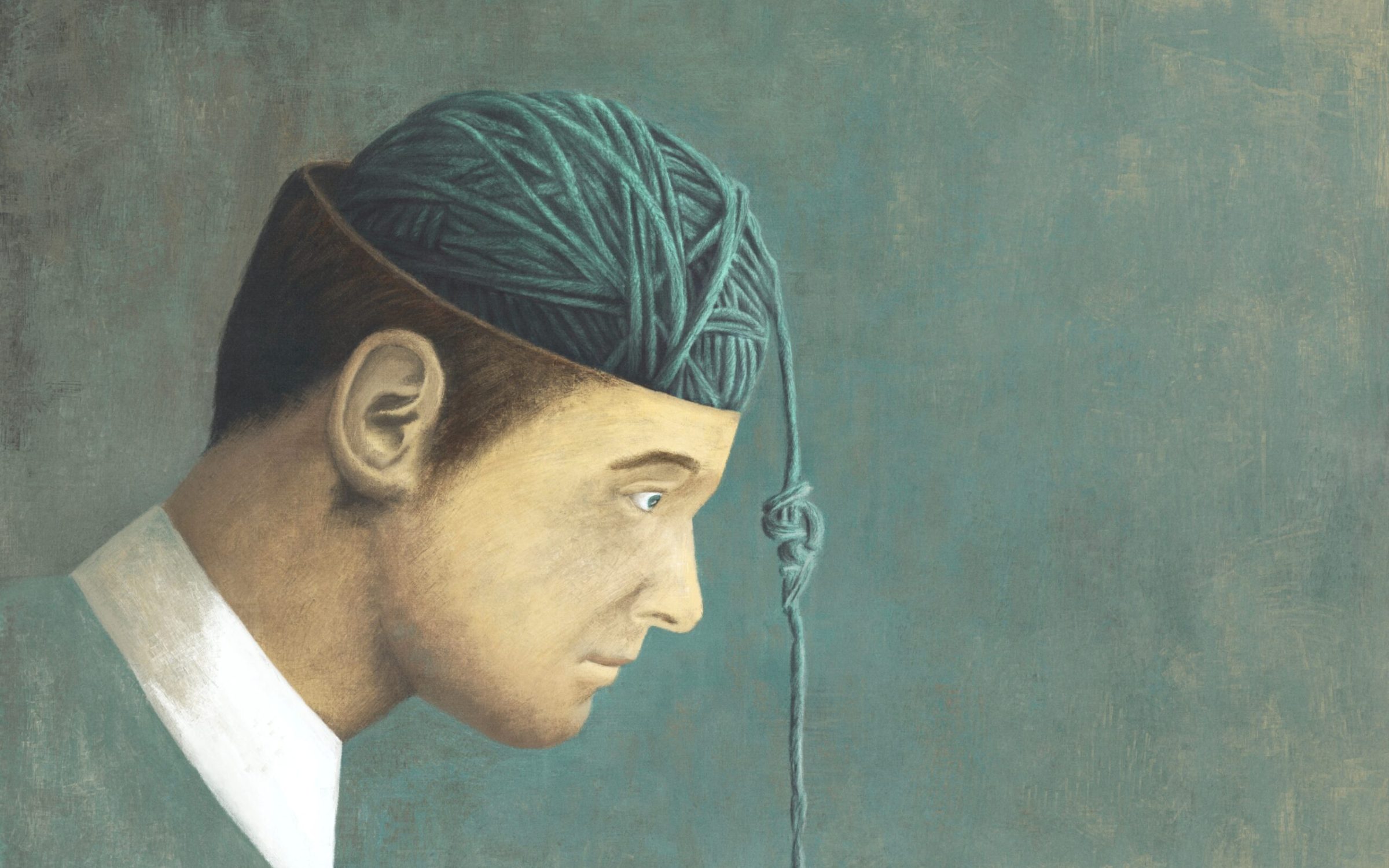

Why has this opening up not helped matters? With the last decade seeing a rapid expansion of the mental health industry, it is unsurprising that a prospective Labour government that has much sympathy with the “be kind” movement would subscribe to it wholesale as the cure to male suicide. This would, however, fail men’s mental health by reducing the complexity of emotional and economic life to a facile, monocausal narrative that obfuscates the conditions that make male suicide more likely. Whatever the problem, the thinking seems to go, it can be solved through speech therapy.

Whilst suicide is the biggest killer of men under the age of fifty, this is fortunately because modern man is unlikely to die of much else before that age. This is not to say that suicide is not a problem. But lining up toxic laddishness and prideful reticence as the usual suspects in the “crisis of masculinity” dilutes and detracts from the seriousness of preventable suicide cases.

Addressing the problems that exacerbate suicide risk factors is, as Ben Sixsmith writes in Quillette, a “more difficult, less marketable and yet more essential” task than simply demanding men open up more. Year on year, rural areas which have been hit the hardest by deindustrialisation, declining living standards and family breakdown are those where suicide rates are the highest in England and Wales. Yet rather than addressing a broader cultural and economic malaise felt hardest by the working classes in the provinces, political elites (in areas which, incidentally, record the lowest rates of male suicide) not only continue to misdiagnose the problem but suggest ineffective and potentially harmful courses of action. Yes, a problem shared can be a problem halved, but to assume that emotional repression is the primary cause of male suicide is totally misguided.

It is a lot easier to pay a footballer to campaign about the importance of opening up, than, say, to build an economy that creates enough well-paid jobs for people without degrees, thereby restoring a sense of purpose and dignity to communities decimated by globalisation and shifting economic patterns. Nevertheless, so wholeheartedly have we adopted the language of therapy, pathologised ordinary emotions and encouraged identity with neuroses that the material conditions which contribute towards depression, loneliness, and suicide are seldom sat down on the leather couch and interrogated themselves.

There is a real paucity in the cultural imagination here. As we exported industry abroad, we continued to import a thoroughly Americanised substitute for the soul of the nation. So lacking in an authentic shared vocabulary to talk about the realities of social decay, that we import cheap psychological concepts, which are low-resolution and blurry at the edges.

Mental health, that unfortunate catch-all term for our life of the mind, has become another self-serving game in the lucrative victimhood racket. After all, why do the unrewarding, and ostensibly callous, work of challenging the consensus view that we need to open up, when you could do a sponsored bungee jump to raise awareness and your own clout on LinkedIn?

Men deserve better than another shallow campaign about the need to “break the stigma”. The stigma right now is in candidly discussing the material conditions that make men miserable, not the mental ones. It is ironic, or perhaps all too expected given the therapeutic currents of progressive thought, that the Left is only concerned with the latter.

Write to us with your comments to be considered for publication at letters@reaction.life